The Influence of Regional State Actors in Afghanistan’s Political Stability

Aidan Parkes

Introduction

This report explores the influence of regional state actors in Afghanistan’s political stability post-2001. The report focuses on armed extremism and the Afghan opium economy as the two primary factors of instability. The first section employs mainly qualitative research methods to draw conclusions whilst the second section by contrast uses quantitative methods of research. Primary sources such as Wikileaks’ ‘Diplomatic Cables’ and ‘The Afghan War Diary’ are used in conjunction with informal interviews. This data is triangulated by secondary sources such as papers by the Brookings Institute and prior academic scholarship. The second section’s employment of quantitative correlational research uses data sourced from the World Bank, IMF, Transparency International and Global Research Centre to synthesise relevant findings. The findings are presented through theoretical frameworks within international relations theory. Barry Buzan’s ‘regional security complex theory’ and the zero-sum game theory are used to fuel the analysis. All quantitative findings can be found in the list of figures. The findings in the report show strong linkage between the Saudi ruling elite and Islamic charities that directly support terrorism in Afghanistan. The terrorist groups in question express foreign policy sentiments that directly align with those of Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, members of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency continue to liaise with, and provide financial support to the elements of the Taliban. The precise extent of Pakistan’s relationship with the Taliban is unknown although it is possible recent changes in Taliban senior leadership were orchestrated by the ISI for greater influence. Afghanistan’s opium economy is exacerbated by the inability of Tajikistan to curb its institutional corruption and improve its border control. The wider Central Asian region has a systemic problem with corruption, which has historically intertwined itself with the regions opium trade. The report finds that whilst the root of Afghan instability is multifaceted and historically subjective, the prospects of stability in the future are contingent upon regional cooperation and dialogue.

Saudi Riyal-Politik

Many extreme militants in Afghanistan and Pakistan have been politically and militarily active since the Soviet occupation. Whilst certain elements of the resistance could be considered opportunists, profiting from lawlessness through the opium or arms trade, some persistent elements within the resistance are motivated by ideology above all else. Indeed the ultimate motivation of ideology is a salient commonality amongst this faction; however, the exact ideologies shared are vastly heterogeneous. Certain religious orientations such as Salafism are far from autochthonous to the South Asian region, which begs the questions, how did such an ideology find its way to Afghanistan? And how complicit is the state that systematically sponsors its spread around the world? This chapter will explore the link between Saudi Islamic charities and extremist groups in Afghanistan.

Salafism

Salafism is an ultra-conservative movement within Islam that is based on fundamentalism. It is uncompromising in its rejection of all other interpretations of Islam, specifically Shiism [1]. Whilst Salafism is practised and prevalent around the world, its most unitary economic, political and social institutionalization is found within the government of Saudi Arabia. It is estimated since 1960 the Saudi government has invested over USD $100 billion into schools, mosques, charities and institutions that propagate Salafism. The enormity of this investment becomes clear when compared to the estimated USD $7 billion invested in the spread of Communism by the Soviet Union over 70 years [2].

Riyadh’s Soft Power Support

A Wikileaks cable titled ‘Extremist recruitment on the rise in Southern Punjab’ outlines how Saudi money makes its way to ostensible Islamic charities, through to extreme clerics who recruit teenagers of low socioeconomic means. The recruits are sent to madrassas in exchange for remittances paid to their family [3]. These madrassas teach a dogmatic interpretation of Islam that is highly critical of the West and the Pakistani government. There is heavy emphasis on Jihad and martyrdom, particularly through suicide missions against ISAF forces in Afghanistan, and Shiites on either side of the Durand line [4]. The cable authored by US diplomat Bryan Hunt, named two complicit charities in particular, Jamaat ud-Dawa and the Al-Khidmat Foundation [5]. Jamaat ud-Dawa is the political and charitable wing of Lashkar-e-Taiba, the terrorist group behind the 2008 Mumbai bombings. Abdullah Azzam, a conceptual founder of al-Qaeda is also credited to have founded the group. A Wikileaks cable from then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton revealed strong evidence linking Lashkar-e-Taiba to a charity based in Saudi Arabia [6]. The relationship between JUD and Saudi Arabia appears reciprocal as evidenced by a recent report by the Brookings Institution [7]. JUD’s scope of political activism has shifted from domestic to international as it recently vocalized support for the Saudi-led campaign in Yemen [8]. The apparent Saudi plight in the face of outside threats is received with empathy by JUD, which declares, “Saudi Arabia is the spiritual leader of Muslims and Pakistan is the defensive centre of the Muslims. We will consider defence of Harmain our religious obligation” [9]. JUD considers Saudi Arabia’s military campaign in Yemen to be a defensive one, and the defence of holy sites a requirement of all Muslims [10].

LeT has continued to cause instability in Afghanistan over a decade after 9/11. The group has been known to liaise quite extensively with al-Qaeda and the Taliban [11]. LeT has been responsible for a number of attacks in Afghanistan targeting Indian targets, highlighting an agenda that is consistently pro-Pakistan [12]. The second group mentioned by Hunt, Al-Khidmat is the largest NGO in Pakistan, which is believed to facilitate the link between impoverished youths and extreme madrassas [13]. It is believed that after the 2005 Kashmir earthquake, Al-Khidmat utilised its position close to those in the direst circumstances, to offer USD $6500 per son to those families who sent their adolescent males to the madrassas [14]. Al-Khidmat is also alleged to have made a one-off donation of $100,000 to Hamas in 2006, underscoring the charity’s consistent extremist stance [15]. The charity facilitated the release of 2500 Taliban and al-Qaeda members as part of an amnesty arrangement by the Pakistani government. Both charities exercise destabilising effects on Afghanistan’s struggle with extremism, and a more widespread pro-Saudi stance evidenced across the Middle East region.

The evidence points not only to a complicit Saudi Arabia, but also to a lack of oversight regarding Islamic charities. The nexus between charities and terrorism appears to have the tacit endorsement of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. This nexus is part of larger ideological amity between the two states that has influenced Pakistan’s education system [16]. Although the militant groups mainly operate in Pakistan and India, it is evident their aggressiveness has impeded Afghanistan’s efforts toward stability. The targeting of Indian infrastructure in Kabul undercuts Afghanistan’s ability to establish future bilateral relations and dissuades foreign and local investment prospects. It is evident both through the investigative data presented and the consistent pro-Saudi stance of Jamaat-ud-Dawa that the financial and ideological support that originates from the Arabian Peninsula has directive from the Saudi ruling elite. The precise extent of this influence remains unknown due to the blurred lines between public and private sector that pervade the Gulf States, and the lack of regulation within Islamic charities. The sectarianism that plagues Af-Pak society will persist so long as Saudi Arabia continues to support dogmatic anti-Shiite causes.

Realpolitik in Pakistan

Raison d’état – Reason of the State

The United States and many other foreign powers, including Pakistan, supported the Mujahideen against the Soviets in Afghanistan. However, when the United States severed relations with the Taliban, Islamabad proved old habits die-hard for those within its military circles, and continued to support the group covertly. This chapter will discuss how Pakistan has contributed to the destabilisation of Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban. The first section will explore the attitudes and sentiments of the Pakistani military, and how Indo-Pak competition has clouded Islamabad’s Afghanistan policy. The second section will discuss how Pakistan uses the Haqqani Network as its ‘veritable arm’, and how Mullah Mansour’s ascension to Taliban leadership indicates a move towards cooperation with Islamabad.

Pakistan’s foreign policy has had a consistent theme of zero-sum game competition with India since the Partition of the British Indian Empire. Afghanistan has thus been manipulated as a substantial component of Islamabad’s larger competition with New Delhi. Pakistan’s foreign policy and strategy were devised in a time of high alert due to the nuclear race with India and the conflict in Kashmir. The Pakistani Military played a large role in politics and its Realist orientation soon transformed into political rhetoric.

“Pakistan’s generals have retained a bedrock belief that, however unruly and distasteful Islamist militias such as the Taliban may be, they could yet be useful proxies to ward off a perceived existential threat from India. In the Army’s view, at least, that threat has not receded” [17].

The policy of ‘strategic depth’ was pursued by numerous ISI and Pak-Mil leaders throughout the Cold War, and openly praised by General Asad Durrani. Strategic depth was initially conceptualised as the distance between the battlefront and key infrastructure such as large civilian populations and government epicentres [18]. It is not limited to military might and includes societal factors such as demographic amity and alliance structures. Pakistan’s preoccupation with strategic depth, as put by former Pakistani president Musharraf, included focus on establishing a “friendly government” in Kabul [19]. Strategic depth theoretically looks to gain influence over economic and security decision-making through subverting a state’s sovereignty [20]. The actualization of such government would focus on high Pashtun representation, and an overall emphasis on Islamic unity. Zero-sum game theory, which Pakistan has applied to the global system more consistently, states that for one person or entity to gain, another must lose [21]. In an interview with Al Jazeera in 2015, General Durrani made several offhand comments alluding to such sentiments. In response to the assertion that the United States gave billions to Pakistan who in turn gave that money to the Taliban to target the U.S, Durrani replied, “So we fooled them, no harm in doing that”[22]. When asked about Pakistan’s apparent duplicity Durrani responded by stating, “If you cannot ride two horses, you have no business to join the circus. These states play double games, and if we did this successfully I suppose this is in the nature of this game” [23].

The historical context of Indo-Pak power competition provides vital insight into the rationale behind Pakistan’s Afghanistan policy. The way the Pakistan military sees the world and its influence in the political realm is inextricably linked to its modern conduct and liaison with the Taliban.

The Haqqani Link

The Haqqani Network is an autonomous Islamist group aligned with the Taliban that operates in Khost, Paktia and Paktika. In response to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, the affluent Haqqani family proved astute at forging relations with the Pakistan ISI, CIA and Gulf donors [24]. The Haqqani family has close ties to the ISI and has historically acted as a link between elements of the Taliban and the ISI. The Network acts out of pragmatism over piousness in its business and military ventures [25]. The group is said to control between 10-25% of all legal and illegal business along its border [26]. The Haqqani do so by investing in real estate in the Middle East and Asia, exporting chromite to China and controlling trucking routes between Afghanistan and Pakistan [27]. The group’s pragmatism has historically been a point of common ground for collaboration with the ISI. The Haqqani Network is the most salient example of Pakistan’s interference in Afghanistan. It has carried out specific attacks against U.S and Indian interests and avoided conflict with Pakistan forces on the border [28].

“The Haqqani network acts as a veritable arm of Pakistan’s ISI agency. With ISI support, Haqqani operatives conducted the attack on our [the United States’] embassy. Choosing to use violent extremism as an instrument of policy, the government of Pakistan and most especially the Pakistani army and ISI jeopardise not only the prospect of our strategic partnership, but Pakistan’s opportunity to be a respected nation with legitimate regional influence”[29].

The Ascension of Mullah Mansour

The death of Mullah Omar and the subsequent promotion of Mullah Mansour indicate a shift towards increased cooperation between the ISI and the Taliban. Mullah Omar created the Taliban in coordination with the Pakistani government against Soviet forces. He was trained by the ISI and liaised with them extensively after the occupation, although his relationship with the ISI was not shared throughout the Taliban. Certain factions were sceptical of foreign help whilst others were happy to entertain mutually beneficial agreements [30]. The disparity within the Taliban reached its zenith with the death of Mullah Omar. The installation of Mullah Mansour makes the Taliban’s collaboration with Pakistan more feasible than with other possible successors to Mullah Omar [31]. As part of the Quetta Shura, sources claim Mansour had “direct influence” over military operates in Khost, Paktia and Paktika, the Haqqani Network’s base [32]. In lieu of choosing a religious scholar or provincial leader, Mansour chose Sirajuddin Haqqani as his deputy [33]. The move towards Haqqani and by effect, towards Pakistan indicates a shift from the dogmatic ethno-religious principles of the Taliban, towards are more versatile group willing to compromise ethics for tangible gain. The decision to appoint Mansour was received with disdain by elements within the Taliban. One senior member of the Quetta Shura told TOLOnews “Mullah Mansour has been appointed by ISI as the successor Mullah Omar and we do not accept this decision”[34]. Rival groups such as the Islamic State’s Khorasan branch have pointed out the relationship between the Pakistani government and the Taliban [35]. ISIS described its recent confrontation with the Taliban as a fight with “hundreds of ISI mercenaries acting in the name of the Taliban’s emirate”[36]. It is likely Mansour’s appointment was orchestrated by the ISI as a more conducive step towards covert cooperation. With the Haqqani Network now at the centre of Taliban decision-making, the group is likely to compromise its ideological and territorial objectives for well-compensated operations, more in line with Islamabad’s regional strategy.

Mutual Gain

The Taliban complements Pakistan’s strategic depth policy, and its general perspective of the international system. The Taliban undermine Indian inroads into influencing Afghanistan and in return Pakistan is able to provide sanctuary and often impunity to its fighters. Interviews conducted by Waldman (2010) suggest the Quetta Shura is facilitated and maintained by the ISI [37]. This is most likely due to the longstanding history between the Taliban and the ISI, and shared Pashtun ethnicity. The asymmetric relationship allows Pakistan to ostensibly arrest Taliban figures when they’ve breached an agreement or are close to U.S/ISAF apprehension. Conversely, the Taliban are able to carry out operations that are conducive to Islamabad’s grand strategy in a fashion that is typically not permissible for a state to undertake.

Opium Economic Instability

Afghanistan produces around 90% of the world’s opium [38]. Surrounded by economically weak and institutionally corrupt states, the opium economy not only destabilises Afghanistan, but the wider region in general. This chapter will outline how rampant corruption within post-Soviet states fuels Afghanistan’s opium problem. The regional security complex theory will be utilised to critically analyse the interdependence of the states within the region. Specific focus will be cast upon Tajikistan and how the organised crime embedded within society aggravates Afghanistan’s opium problem.

Afghanistan’s Illicit Economy

The Opium economy in Afghanistan destabilises the state as it offers a means of income that operates outside the legal economy. In some respects, the opium economy operates in competition with the legal economy particularly in the agricultural sector. It competes with the legal economy in that opium poppies offer a more lucrative option for farmers than the legal alternatives such as wheat, pistachio and saffron crops. Depending on global drug markets, opium cultivation can prove to be twenty times more profitable than wheat per hectare [39]. In addition to the direct effects on the economy, opium cultivation complements further illegal activity such as banditry, militancy and crime. Rural areas that are plentiful in poppies may be economically susceptible to the rule of law being challenged by militias, private armies and warlords.

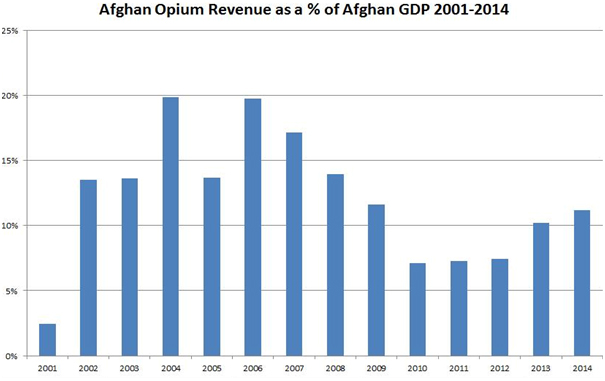

Figure 1

Figure 1 depicts how the opium economy compares to the legal economy; at its peak it reached 20% of the legitimate GDP. An illegal economy of such relative size invariably inhibits economic growth and economic sustainability in Afghanistan. From its initial impediment of fiscal prosperity, it goes on to affect the national budget, sector deficits, and the creation of new jobs [40].

The influence of regional state actors in the Afghan opium trade is different from that of the insurgency analysis in that it is not a strategic calculation. Rather, the inabilities of states in the region hinder Afghanistan’s plight with drug trade. The regional security complex provides a holistic lens through which the enormity of the drug trade can be properly understood. Because of the comparatively austere narcotics control along the Iran border and a large prospective consumer base north towards Russia, much of Afghanistan’s opium is circulated through Central Asia (CA). The Central Asian states constitute a distinct security complex, in which Barry Buzan considers Afghanistan to be a buffer state [41]. However, utilizing the RSC theory to explore Afghanistan’s destabilisation by the opium trade, it can be included within such complex. Because of historical factors such as corrupt governance, harsh economic conditions, civil war and reliance on the Soviet Union, the CA states have struggled to control their borders and establish the rule of law. This incapacity has allowed the opium economy of Afghanistan to thrive, and intrinsically links Afghanistan to the Central Asian security complex.

Tajikistan

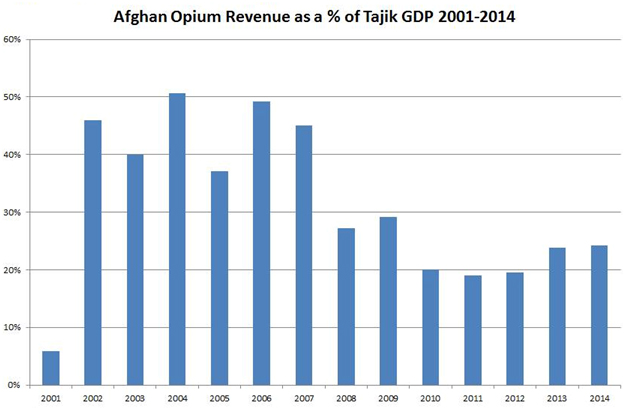

Figure 2

Transparency International ranked Tajikistan the 32nd most corrupt nation in the world with all neighbours except China ranking within the top 50 [42]. The corruption in Tajikistan has aggravated Afghanistan’s drug crisis as both a transit route and customer base. 80% of all narcotics produced in Afghanistan transit through Tajikistan [43]. The Afghan opium trade has become so deeply embedded within Tajikistan’s economy that neither can function without the other [44]. Figure 2 shows the size of the estimated Afghan opium economy against the GDP of Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Kyrgyzstan. Because of the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Tajik Civil War, the Afghan opium economy went further in undermining the Tajik economy, by rivalling it in many respects [45]. Criminal syndicates and warlords who formed the Tajik opposition in the civil war had long wielded power in their respective regions through modern fiefdom within a pseudo-patrimonial society [46]. The narcotic trade was vital to their power in the region, and was institutionalised when a UN peace agreement gave 30% of all government positions to the Tajik Opposition [47]. Indeed, the warlords had become nominal civil servants; however, they failed to relinquish their prior racketeering [48]. As Cokgezen (2004) sees it, there is a distinctly ‘eastern’ characteristic to Central Asian corruption, which he believes is ingrained in society and family structures [49]. The somewhat customary prevalence of bribery complements the opium trade in Tajikistan through a system that tacitly encourages it. As figure 2 evidences, the opium economy has the monetary power to challenge Tajikistan’s legal economy. Customary bribery coupled with inadequate salaries of Tajik border police make them susceptible to bribery and systematic corruption.

“Nearly all law enforcement and border patrolling officers in the border districts are involved in drug trafficking. Some of them smuggle drugs into Tajikistan; others deliver drugs from border districts to other parts of the country; others still ‘open’ the border to traffickers or provide them with crucial information. In other parts of Tajikistan the percentage of corrupted officers is lower. In my opinion, eight officers out of ten are corrupted in Dushanbe” [50].

-Anonymous Tajik official

The modern Tajik state has developed in conjunction with the Afghan opium economy. As Figure 2 shows, during the formative years of Tajik statehood, the opium economy reached fluctuating levels between 30-50% of the legitimate GDP. Drug trafficking throughout Central Asian continues to find tacit acceptance within factions of Tajik government, the extent of which is unknown. Although Dushanbe is not to blame for Afghanistan’s opium economy, if it were to address seriously the corruption that plagues its government, the benefits would no doubt be felt in Kabul.

Implications of the RSC on Afghanistan’s Opium Economy

Figure 3

The Central Asian regional security complex places the Afghan opium economy in a position where is it likely to thrive and persist. It is the particular institutionalisation of corruption within the post-Soviet states that lubricates the drug economy of the region and makes the syndicates that much harder to eradicate. The blurred lines between warlord and civil servant and public and private sector have persisted for so long that the acceptance of drug trafficking has become characteristic of the region, much to the detriment of Afghanistan’s capacity building efforts.

“Corruption is common or expected in countries where the following practices are observed: gift-exchange in business transactions, allegiance to kinship, clan-based loyalties and subordinates highly dependent on their superiors in a paternalistic way”[51].

If it is to be believed that the cultural norms of the Soviet Union are the common denominator in corrupt CA states, the evidence presented in Figure 3 strengthens Cokgezen’s assertion that corruption has cultural explanations. The extent to which the corruption is influenced by such cultural norms is subjective however the link between corruption and drug trade trafficking is not [52]. Afghanistan will not achieve total stability until its opium crisis is quelled. The RSC theory provides an insight into how the transnational problem of drug trafficking is an interdependent problem with regional onus.

Conclusions

Conflict in Afghanistan has been exploited and exacerbated for external gain. Saudi Arabia’s support of extremism gains traction through ideology but complements its wider geopolitical goals. Pakistan’s official declaration of severed relations with the Taliban is ostensible at best. Islamabad’s support of the Taliban is possible due to the overarching influence of its military. The scale of violence in Afghanistan suggests that Pakistan’s support for the Taliban is a product of state policy and that the responsibility of the conflict cannot be blamed on rogue elements within the ISI. The conflict’s enduring nature is due to its foreign support and prospects of peace will only be feasible when this foreign support is relinquished. Central Asian states, notably Tajikistan exacerbate the effects of Afghanistan’s opium economy through incapacity rather than the duplicity exhibited by Pakistan. Tajikistan’s systematic corruption enables the opium economy not only to persist but also to thrive. For Afghanistan’s opium economy to be controlled, the networks and markets that circulate it must be dismantled.

End Notes

[1] John Esposito ‘The Oxford Dictionary of Islam’ Oxford University Press. (2004) p.275.

[2] 'Tsunami of money' from Saudi Arabia funding 24,000 Pakistan madrassas’ Economic Times of India. (2016) http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2016-01-30/news/70200925_1_saudi-arabia-wahhabi-islam-religious-school

[3] Bryan Hunt ‘Extremist recruitment on the rise in Southern Punjab’. Wikileaks Diplomatic Cables. (2008) https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08LAHORE302_a.html

[4] The Durrand Line is the territorial boundary that separates Pakistan and Afghanistan.

[5] Note: Both charities are large organizations and do a great deal towards terrorist relief.

[6] US embassy cables: Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorists raise funds in Saudi Arabia’. The Guardian. 2010

[7] Christine Fair. ‘Whether or not Pakistan will join the war in Yemen may depend on a group you’ve probably never heard of’ Brookings Institution (2015) http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/markaz/posts/2015/04/14-pakistan-military-assistance-saudi-intervention-yemen

[8] JUD Faisalabad. (@JUDFaisalabad) Translation: Saudi Arabia is the spiritual leader of Muslims and Pakistan is the defensive center of the Muslims. We will consider defense of Harmain our religious obligation.” https://twitter.com/JUDFaisalabad/status/583219092770844672

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] Mariam Abou Zahab and Olivier Roy, ‘Islamist Networks: The Afghan-Pakistan Connection’ New York: Columbia University Press (2004) p.42.

[12] Karin Brulliard, ‘Afghan Intelligence Ties Pakistani Group Lashkar-i-Taiba to Recent Kabul Attack’ Washington Post, March 3 (2010)

[13] Bryan Hunt ‘Extremist recruitment on the rise in Southern Punjab’. Wikileaks Diplomatic Cables. 2008

[14] Ibid.

[15] R Muaro ‘North Carolina Smuggling Ring Linked to Muslim Brotherhood’ (2014)

[16] A.H. Nayyar and Ahmed Salim, eds., ‘The Subtle Subversion: The State of Curricula and Text books in Pakistan’ (Urdu, English, Social Studies and Civics) Islamabad: Sustainable Development Policy Institute, (2002)

[17] Steve Coll ‘War by Other Means’ The New Yorker (2010) http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/05/24/war-by-other-means

[18] Qandeel Siddique. ‘Pakistan's future policy towards Afghanistan’. Danish Institute for International Studies. (2011)

[19] Musharraf sought ‘friendly government’ in Kabul post 9/11’ NDTV (2011) http://www.ndtv.com/world-news/musharraf-sought-friendly-government-in-kabul-post-9-11-467341

[20] Moeed Yusuf, Huma Yusuf and Salman Zaidi, ‘Pakistan, the United States and the End Game in Afghanistan: Perceptions of Pakistan’s Foreign Policy’. Islamabad and Washington, DC: Jinnah Institute and the United States Institute of Peace (2011)

[21] Joshua W. Walker ‘Introduction: The Sources of Turkish Grand Strategy – ‘Strategic Depth’ and ‘Zero-Problems’ in Context’ (2011)

[22] Head to Head – Pakistan: Victim or Exporter of Terrorism?’ Al Jazeera English. Youtube.com (2015) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z__lyS-wI7c

[23] Ibid

[24] Questions Raised About Haqqani Network Ties with Pakistan’ International Relations and Security Network. (2011)

[25] Ibid

[26] Gretchen Peters ‘Haqqani network financing: the evolution of an industry’ Military Academy West Point NY Combating Terrorism Center, (2012) P.45

[27] Maj. Lars Lilleby ‘The Haqqani Network: Pursuing Feuds Under the Guise of Jihad?’ Global Ecco. (2014) https://globalecco.org/the-haqqani-network-pursuing-feuds-under-the-guise-of-jihad#26

[28] Jalil Ahmad ‘Militants attacks Indian consulate in Western Afghanistan’ Reuters (2014) http://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-india-idUSBREA4M02Y20140523

[29] US Admiral: “Haqqani is veritable arm of Pakistan’s ISI” BBC News (2011) http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-15026909

[30] Jawed Zeyartjahi ‘Taliban’s Splinter Group Rise Up Against Mansoor’s Fighters in Badghis’ Tolo News. (2016) http://www.tolonews.com/en/afghanistan/24368-talibans-splinter-group-rise-up-against-mansoors-fighters-in-badghis-

[31] Bill Roggio ‘New Taliban emir accepts al Qaeda’s oath of allegiance’ (2015). http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/08/new-taliban-emir-accepts-al-qaedas-oath-of-allegiance.php

[32] Praveen Swami ‘New Taliban chief Mullah Akhtar Muhammad Mansour oversaw IC-814 ops at Kandahar’ The Indian Express. (2015) http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/new-taliban-chief-mullah-akhtar-muhammad-mansour-oversaw-ic-814-ops-at-kandahar/

[33] Saleem Mehsud ‘Kunduz Breakthrough bolsters Mullah Mansoor as Taliban Leader’ Combating Terrorism Center. (2015) https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/kunduz-breakthrough-bolsters-mullah-mansoor-as-taliban-leader

[34] Sayed Kazemi ‘Mullah Mansour an ISI Appointment: Taliban Quetta Shura’ TOLOnews (2015). http://www.tolonews.com/en/afghanistan/20684-mullah-mansour-an-isi-appointment-taliban-quetta-shura

[35] Thomas Joscelyn ‘Islamic State ‘province’ claims attack on Pakistani consulate in Jalalabad’ Long War Journal (2016) http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2016/01/islamic-state-province-claims-attack-on-pakistani-consulate-in-jalalabad.php

[36] Ibid

[37] Matt Waldman ‘The Sun in the Sky: The Relationship Between Pakistan’s ISI and Afghan Insurgents’ Crisis States Research Centre (2010) http://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Documents/2010/6/13/20106138531279734lse-isi-taliban.pdf

[38] Elizabeth Chuck ‘Heroin use grows in U.S, Poppy Crops Thrive in Afghanistan’ NBC News. 7 July (2015)

[39] Byrd, William A.; Buddenberg, Doris. ‘1: Introduction and Overview’. Afghanistan's Drug Industry Book: Structure, Functioning, Dynamics and Implications for Counter-Narcotics Policy’ (PDF). http://www.unodc.org/pdf/afg/publications/afghanistan_drug_industry.pdf

[40] ‘The Opium Economy in Afghanistan: An International Problem’ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2003) https://www.unodc.org/pdf/publications/afg_opium_economy_www.pdf

[41] Felix Ciută Reviewed work(s): ‘Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security by Barry Buzan; Ole Wæver, The Slavonic and East European Review’, Vol. 83, No. 1 (Jan. 2005), pp. 166-168.

[42] Corruption by Country: Tajikistan’. Transparency International, (2016). https://www.transparency.org/country/#tjk

[43] John Engvall, ‘the state under siege: The drug trade and organized crime in Tajikistan’. Europe-Asia Studies 58/6 (2006) p.828

[44] Letizia Paoli, ‘Tajikistan: The Rise of a Narco-State’ The Journal of Drug Issues. (2007) https://lirias.kuleuven.be/bitstream/123456789/200273/1/Paoli%20et%20al._Tajikistan_printed%20article.pdf

[45] Christian Bleuer and Said Reza Kazemi ‘Afghanistan’s Relations with the Central Asian Republics’, (AAN Report 1, Afghanistan Analysts Network June 2014) pp. 1-74.

[46] Kiril Nourzhanov 'Saviours of the Nation or Robber Barons? Warlord Politics in Tajikistan', Central Asian Survey, vol. 24, no. 2, (2005), pp. 109-131.

[47] Letter dated 1 July 1997 from the Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General (1997) http://www.un.org/Depts/DPKO/Missions/unmot/prst9757.htm

[48] Antonio Giustozzi. ‘Respectable warlords? The transition from war of all against all to peaceful competition in Afghanistan’. Research Seminar 29 January. (2003) http://www.crisisstates.com/download/others/SeminarAG29012003.pdf.

[49] Murat Cokgezen. ‘Corruption in Kyrgyzstan: The facts, causes and consequences’. Central Asian Survey, 23(1), (2004) pp.79-94.

[50] Letizia Paoli, Victoria A. Greenfield, and Peter Reuter. ‘The world heroin market: can supply be cut?’ Oxford University Press, (2009). P.957

[51] Murat Cokgezen. ‘Corruption in Kyrgyzstan: The facts, causes and consequences.’ Central Asian Survey, 23(1), 79-94. (2004)

[52] Adirana Rossi ‘Crime in Uniform: Corruption, Drug Trafficking and the Armed Forces’ Transnational Institute (1997)

Interviews Conducted

Abbas Farasoo – chargé d'affaires, The Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan April 10 2016

Professor William Maley – Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy May 6 2016

Nishank Motwani – Doctoral Candidate UNSW May 6 2016

Akhi Pillalamarri – The Diplomat (editor) April 26 2016