Special Operations Support to Conflict Prevention

Assad A. Raza

"Preventing the collapse of a state where the infrastructure is under immense strain can save a country from mass slaughter of civilians, violent conflict, and gross abuses of human rights. Thus, prevention is tied into the need to avoid human suffering in certain states, and the need to prevent violence from taking place.”

-- Jacob Bercovitch and Richard Jackson1

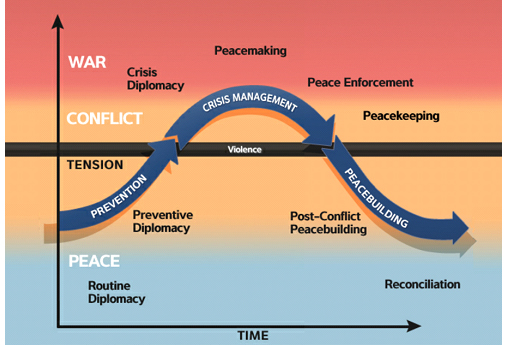

Figure 1: United States Institute of Peace (USIP) Curve of Conflict2

Introduction

Soon after the end of the Cold War, political expert Samuel P. Huntington wrote an article titled “The Clash of Civilizations” in 1993. Huntington emphasized how globalization contributed to the increased tensions between different cultures, as societies feared their values and identities were threatened. Fast forward 24 years and populist nationalism and violent extremism are growing all over the world. Significant and lasting diplomatic issues can be correlated to technological advancements, which amplify these sentiments globally. In Europe, the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union and the threats by France’s nationalist party to withdraw from the EU during their recent elections demonstrates the weight popular sentiment carries through many nations. In the Middle East, the world witnessed the Arab Spring as an underemployed and an overlooked demographic—the Arab Street—protested the corruption and human right abuses carried out by their governments.3 Moreover, in Syria and Iraq, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) gained the support of a disenfranchised Sunni population to seize vast amounts of territory between eastern Syria and western Iraq in an attempt to establish a self-governing state, with the intent for a global caliphate. A key contributor to the movements mentioned is the considerable amount of information shared through social media that has increased the rate of globalization and has amplified underlying grievances that lead to violence. As the world is becoming increasingly interconnected, the risk for populist or extremist groups to exploit discontented populations for their interests will continue to grow. For this reason, future conflict will be exacerbated by the effects of globalization and the democratization of technology which intensifies social disparities that were once isolated.

The Concept

In the age of accelerated globalization and its toll exacted on conflict, the United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) should prioritize conflict prevention activities to achieve US national security objectives. According to Joint Publication 3-07.3, conflict prevention is “a peace operation employing complementary diplomatic, civil, and, when necessary, military means, to monitor and identify the causes of conflict, and take timely action to prevent the occurrence, escalation, or resumption of hostilities.”4 For conflict prevention to be successful, it takes a holistic approach, which includes all elements of national power, international partners, and a coordinated policy to implement them. USSOCOM is the only organization within the Department of Defense (DoD) that has the unique capabilities and best-skilled forces with the political, cultural, and regional knowledge to take on the challenge of conflict prevention. This article will focus on special operations forces (SOF) approach towards conflict prevention and the challenges associated with it.

Conflict Prevention

Conflict prevention, also referred to as preventive diplomacy, is a method that’s been discussed by the United Nations, and other international organizations to prevent and manage escalating tensions to avoid conflicts, and to set the conditions for long-term peace and stability. Witnessing the conflicts that arose immediately after the end of the Cold War, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, former UN Secretary General, wanted a more pro-active approach that would reduce the risk of violence and act as an early warning system for areas where conflict appeared imminent. In 1992, Boutros re-prioritized the importance for the UN to change their approach towards conflict prevention rather than focusing on peace-making or peace-keeping, which happens in the aftermath of violent conflicts. However, Boutros’ approach was more focused on prevention rather than addressing the root causes of conflict.5

Authors Carment and Schnabel stated that conflict prevention is a “long-term proactive operational and structural strategy undertaken by a variety of actors, intended to identify and create enabling conditions for a stable and more predictable international security environment.”6 Thus in Carment and Schnabel’s framework, conflict prevention would involve several other US government agencies, international organizations (IGOs), regional organizations, coalition partners, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to create the conditions necessary to prevent conflicts from emerging.

These SOF professionals can focus on a combination of contributing factors such as social, political, and economic grievances and help target those root causes that can lead to violence. However, to successfully implement this approach, it requires an integrated strategy in which SOF would play a supporting role. SOF can assist other agencies and local/regional partners by monitoring the information environment to identify early signs for potential conflicts, assist partners with social and economic initiatives, and work with local partners on strategic communications to promote stability and dissuade support to competing actors. In this role, SOF can also, collaborate with state and local indigenous partners to build trust between conflicting parties and identify any potential signs of violence before they erupt.

The Internet

Social media has been a major contributor in influencing political outcomes, mobilizing demonstrations, and instigating conflicts. To gain a better understanding of the contributing factors for violence, SOF can assist other agencies and local partners with collecting, monitoring, and analyzing information across multiple networks to identify early signs of conflict in high-risk areas. These activities can be accomplished through the host nation, international organization, or coalition of regional partners. Social media as a communication platform provides real-time updates with changes in the political sentiment of a population, human rights violations, or economic inequalities, often overlooked before the internet. This platform can be used to collect evidence and hold governments or other actors accountable for their actions and undermine their repressive efforts. The information gathered and analyzed through social media can help predict conflict and provide time for SOF partners to develop a preventive response.

Further, SOF can assist partners in developing cyber strategies to illuminate illegal cyber activities and counter adversarial propaganda that promote conflict. These activities would include coordinated information operation efforts in support of host nation, regional partners or IGO/NGOs to counter adversarial propaganda and disinformation. If necessary, SOF can assist with coordinating for offensive cyber operations to prevent or deny actors from carrying out illicit activities from high-risk areas or weak states. Cyber operations can be used to remove adversarial websites to sabotaging their sites disrupting finance and recruitment efforts. Looking forward, conflict prevention through the cyber domain can be seen as low risk with high returns, which doesn’t play into our adversaries’ counter-narratives if there is no physical evidence of the initiator.

Informational Activities

A crucial component for deterring violence is the integration of Military Information Support Operations (MISO) to help prevent conflicts. As mentioned earlier, globalization and technology have drastically changed the information environment. Now state and non-state actors can saturate the information environment to exploit underlying grievances and encourage violence. MISO should be used to assist indigenous partners to develop themes and messages that help prevent conflict and promote stability. Messages should be disseminated through all means (social media, TV, radio, print) available to reach those high-risk populations. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan's anti-extremism radio program managed by the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF) Director of Moral Guidance provides an example of the use of information to prevent violence. JAF radio programs that promote stability can be heard all throughout the country 24hrs a day via the traditional radio stations, Android applications, and social media, through the official JAF Facebook page.7

In an interview, the Director of Moral Guidance Brig. Gen. Abdullah Huneiti said, “The popularity of radio makes it an effective tool to increase national awareness and mitigate the impact of propaganda, disinformation and destructive rumors.”8 The use of all communication platforms has extended their reach to disseminate positive messages in areas vulnerable to extremist ideology. This approach can be replicated in conflict prevention efforts to build partner capacity and provide a capability to counter messaging that promotes conflict in vulnerable areas.

Overall, the use of messaging and technology to prevent conflicts must be synchronized with other programs that directly address the root causes that fuel violence. Examples of this are reconciliation programs that address grievances or public apologies for crimes relating to human rights violations imposed by another group or government.9 Amplifying these positive efforts can influence discontent populations to not support competing actors and minimize the risk of violence. In theory, if relations between conflicting groups increase, it will diminish competing actors’ opportunities to exploit grievances and improve reporting on their illicit activities.

Civil-Military Operations

In addition to messaging, it is crucial for SOF to coordinate with interagency partners, IGOs/NGOs, and the indigenous population to gain an understanding of the underlying causes of instability. Civil Affairs forces can support these efforts by facilitating dialogue with all parties involved to ensure information sharing and a common operating picture of all efforts. Historically, the UN or regional organizations, usually take the lead in conflict prevention. They are typically better equipped to assist with economic, developmental, and humanitarian assistance.10 However, most international or regional organizations start at the national level and require time to develop grassroots relationships. When it comes to local grievances, NGOs have greater access to real-time information due to their close work with indigenous communities. According to Pamela Aall, a senior advisor to Conflict Prevention and Management at the US Institute of Peace (USIP), “NGOs have a crucial function to perform in preventing violent conflicts from emerging, as they are often already working with grassroots and civil society organizations within communities.”11 Thus, NGOs are usually better positioned to recognize conditions that can lead to conflicts. For this reason, it is essential for Civil Affairs forces to coordinate with these organizations to gain a better understanding of the grievances that contribute to instability. Civil Affairs forces can manage the civil information gathered and support partners with developing ways to mitigate underlying causes of instability. The sharing of information among all actors also promotes trust and establishes a unified effort towards conflict prevention. A unified effort to address the grievances of all parties involved is necessary to prevent conflicts and human suffering. Normally, this is a short-term response, as this only provides time for other organizations to implement a more long-term approach towards governance, economic development, and social reforms.

Civil Affairs forces with their cultural and regional knowledge can develop relationships with indigenous leaders to identify those moderate partners who are necessary for the success of preventative efforts. Engagements with local communities and collection of civil information can be used to validate the grievances and needs of the populations in different areas. The cross-pollination of civil information with other organizations is important because each community will have different needs and perceptions of issues that contribute to the instability. More importantly, Civil Affairs forces can facilitate the coordination between local authorities and other organizations to provide necessary assistance in vulnerable areas that may have been overlooked. These relationships may help create a safe and positive environment which will lead to future reconciliation efforts between conflicting parties. Engaging at the grassroots level will also disrupt competing actors’ opportunities to exploit grievances, and provide a better understanding of the frustrations throughout these communities, which is vital in conflict prevention.

Warrior Diplomats

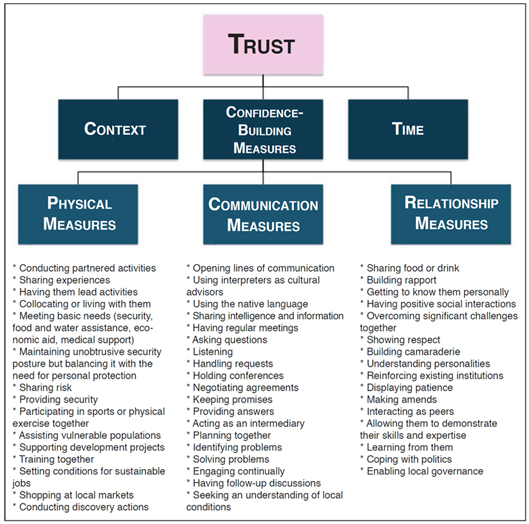

Confidence-building measures (CBMs) are critical components in conflict prevention to reduce anxiety and misperceptions between opposing parties.12 Although CBMs is often implemented at the national levels, SOF can contribute at the tactical level by being a neutral party who encourages cooperation and facilitate activities between conflicting parties to prevent violence. It’s proven that having a neutral force is necessary to deter violence and ensure security agreements or power-sharing arrangements are enforced. Recent examples are the use of neutral troops in Bosnia and Iraq (before the 2011 withdrawal), as the military presence contributed to the political and psychological role in reassuring that opposing parties would not return to violence.13

The US Army Special Forces (SF) are cultural and regional experts trained in Unconventional Warfare and Foreign Internal Defense with the unique skills necessary for CBM. Compared to other elements of special operations, they have the language and cultural skills required to build relationships and conduct successful CBM at the lowest level. CBM are sensitive and precarious missions where troops are engaged with conflicting parties, with potential misperceptions by any one side.

Confidence-building measures demand a good understanding of the culture, history, and root causes of instability to reduce tensions and build trust. SF activities can promote cooperation by; facilitating the exchange of information between conflicting parties; conducting joint training; and advise/assist/ accompany in joint patrols to foster trust amongst their ranks. If the conditions are so tense, then SF can promote transparency by enforcing mutual agreements and provide early warning of conflict escalation. SOF support to CBM strategies provides the groundwork for state-level security cooperation and impedes the emergence of an insurgency that may not agree with a resolution. However, these measures require a long-term commitment. As seen in Iraq from 2011, an early disengagement or withdrawal can cause turmoil leading to an interminable conflict and internecine violence.

Figure 2: Confidence Building Measures in the Contemporary Operating Environment14

The Challenges

While there are several challenges associated with the implementation of successful approaches to conflict prevention, this article illuminates these specific issues: state sovereignty, international support, capacity, required policies, and political will. Understanding these challenges will help senior leadership develop policies required for the timely and effective use of SOF to prevent violence from escalating.

State sovereignty is the most difficult and controversial challenge with conflict prevention. The host nation or state must agree to an early intervention by a third party to implement an approach. This third party requirement is vital to the prevention of further violence and must be identified early on to ensure the necessary resourcing and negotiations for the intervention. Therefore, convincing state leaders to accept third-party intervention in their internal affairs is challenging. Historically, if a host nation does consent, there is a risk for the conflicting party to perceive the support as illegitimate or for competing actors to exploit the situation through popular support and resist the intervention. Therefore to prevent violence from erupting it requires a well-timed and coordinated intervention strategy.

Another challenge is garnering international support necessary for conflict prevention to be successful. Conflict prevention is a long-term commitment by all parties involved, which many countries’ interests nor capacity align to take on such a burden. When a state or organization commits to early intervention, there is a risk that their interests will conflict with US interests or vice-versa in the region. Also when an international partner is compelled to support, that partner may have limited capacity, forcing them to withdraw prematurely, placing pressure on contributing partners to fill the void. As mentioned earlier, a long-term commitment is challenging and costly to maintain. This highlights the importance of comprehensive negotiations early on to seize potential agreements that take preventative action to inhibit escalation.

USSOCOM does not have the capacity to support multiple operations simultaneously. However, depending on the complexity of a mission, SOF may be augmented by conventional forces to meet specific requirements, for example from the new Security Force Assistance Brigades that are being stood up by the US Army. Ideally, efficiency can be gained by working closely with allies like the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia special operations forces. This collaborative approach expands coordination with a broader range of actors, from IGOs/NGOs to local militias, which is necessary for synchronized preventive efforts. Most often, SOF should be in the lead, as conflict prevention requires the unique skills necessary to engage with indigenous populace. At the moment, SOF regularly engage locals in the hinterlands and far-flung jungles to national level government officials in developing countries.

The final challenge to conflict prevention is the lack of political will to invest in preventive efforts, especially in countries most vulnerable to conflict but have no strategic value. The reality is that decisions are influenced by cost to benefit analyses and policymakers determining if support aligns with national interests. Another reason is the US may not want to take on a unilateral operation when other members of an international organization, for example, the United Nations, veto a resolution. Lastly, when the host nation is not willing to support such measures, as mentioned earlier, the US may not apply diplomatic pressure to impose its will, as demonstrated with the withdrawal in 2011 from Iraq.15

Conclusion

The accelerated rate of globalization combined with technological advances can be beneficial in identifying early stages of conflict before it escalates into violence. SOF have a broad range of capabilities to aid in conflict prevention. These measures combined with other military and civilian agencies can set conditions for long-term peace and stability. Moreover, it would be in support of other organizations’ initiatives to improve governance and socio-economic grievances by effectively preventing conflict from occurring. Responding to conflict once violence has erupted is more expensive and puts forces at a greater risk. Identifying global hotspots and providing intervention to reduce violence is cost-effective in the long term, will reduce the threat for mass atrocities from occurring, and mitigate the risk of any spillover into neighboring countries.

In addition to being cost-effective, this approach provides SOF a persistent presence with both local and international troops for an extended period. Advising and assisting peacekeeping forces or indigenous security forces in prevention efforts improves SOF language and cultural skills, preparing them further for other special warfare activities. SOF can use social media to monitor and empower indigenous partners to counter messages and disinformation that instigate violence. They can partner with international and local partners to gather information to gain a granular understanding of what leads to conflict and develop a plan to address those underlying grievances. In sum, for conflict prevention to be successful, it takes an integrated approach with international and regional partners to address social, political, and economic grievances, reducing the effects of regional instability.

End Notes

1. Bercovitch & Jackson (2012) Conflict Resolution in the Twenty-First Century: Principle, Methods, and Approaches, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press 2012

2. The Curve of Conflict was introduced by and adapted from Michael S. Lund, who was a 2011-2012 USIP Senior Fellow.

“Conflict has its own dynamic, and it tends to escalate and recede over time. The curve of conflict helps us to visualize how conflicts typically evolve over time and how different phases of conflict relate to one another. It is one way in which we can deconstruct the dynamic of conflict and seek to understand it and handle it more effectively.”

“Along the curve, we can identify discrete stages where action can be taken to prevent, manage, or resolve conflict, using peacebuilding tools.”

“Understanding where a conflict falls in the cycle is essential to developing effective strategies for these interventions. It is also critical to determining the best timing of those strategies as part of the process of peacebuilding.”

http://www.buildingpeace.org/think-global-conflict/curve-conflict

3. Amnesty International (2016), The ‘Arab Spring’: Five Years On, 01 JAN 2016.

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2016/01/arab-spring-five-years-on/

4. JOINT PUBLICATION 3-07.3 Peace Operations, DATED 25 MAY 2012 https://fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/jp3-07-3.pdf

5. Bercovitch & Jackson (2012) Conflict Resolution in the Twenty-First Century: Principle, Methods, and Approaches, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press 2012

6. Carment & Schnabel (2003) Introduction-Conflict Prevention: A Concept in Search of a Policy, Tokyo: UN University Press 2003

7. Official Jordan Armed Forces Facebook Page, https://www.facebook.com/ArmedForcesJO/

8. Lt. Col. Elena O'Bryan and Staff Sgt. Joseph VonNida (2016) Colorado National Guard observes partner Jordan's anti-extremism radio broadcast programs. https://www.army.mil/article/173915/colorado_national_guard_observes_partner_jordans_anti_extremism_radio_broadcast_programs

9. The Gaurdian (2014) Special Report: Truth, Justice and Reconciliation: An examination of how countries around the world affected by civil war or internal conflict have approached justice.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/24/truth-justice-reconciliation-civil-war-conflict

10. Bercovitch & Jackson, Conflict Resolution in the Twenty-First Century, 96.

11. Aall, Pamela (2001) What do NGOs Bring to Peacemaking? In the book Turbulent Peace: The Challenges of Managing International Conflict, Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace.

12. Bercovitch & Jackson, Conflict Resolution in the Twenty-First Century, 94.

13. Pollack, Kenneth (2016) Fight or Flight: America’s Choice in the Middle East, Foreign Affairs, Vol 95, # 2 March/April 2016

14. Bazin, Aaron, LTC (2014) Trust: A Decisive Point in COIN Operations, Infantry Magazine Jan-Mar 2014.

15. Bercovitch & Jackson, Conflict Resolution in the Twenty-First Century, 99.