Emerald Wars: Colombia’s Multiple Conflicts Won’t End With the FARC Agreement

Douglas Farah

Introduction

As the Colombian government and Marxist guerrillas stumble toward an uncertain peace to end the hemisphere’s oldest insurgency, there is widespread hope that the violence that has defined the nation for much of its history is finally winding down. However, even assuming the best possible outcome for the peace process with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC), other wars will likely continue to pose significant challenges to the governability of the nation.

As past demobilization efforts show, significant segments of non-state armed actors who are supposed to disarm simply move on from ideologically inspired violence to economically driven violence. In Colombia, examples of this include the 2006 disbanding of the right-wing paramilitary United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia – AUC), where many of the former combatants morphed into sophisticated criminal structures like Los Urabeños.[1] And dissidents in the 1991 incorporation of the Popular Liberation Army (Ejército Popular de Liberación – EPL) into the political process in 1991 gave rise to the violent and powerful “Megateo” drug trafficking group.[2]

Of the multiple conflicts that will continue, those revolving around the control of coca plantations, cocaine labs and cocaine routes will draw the most of the limited international attention that will be focused on ongoing violence. This paper looks at one such conflict that has proven to be intractable and largely impervious to efforts to bring peace – the lucrative emerald trade. Historically, the precious stones trade is both economically and ideologically motivated, where cycles of violence periodically erupt out of tenuous peace agreements.

This discussion does not aim to diminish the accomplishment of bringing at least a significant faction of the FARC out of the jungles and into civilian life in the current peace process, although it is likely that a significant number of FARC combatants will continue to operate as armed criminal groups. The challenges of making demobilization of most or even an important part of the FARC a reality represent an enormous undertaking, with no real guarantee of success; yet, getting even a few hundred violent non-state actors off the battlefield is worthwhile.

However, history shows us that the euphoria surrounding the possibility of peace with the FARC, and the widespread belief that such a process would usher in a broader era of peace, is unrealistic and misplaced. Numerous violent actors have been removed in recent decades, from Pablo Escobar to the Cali cartel leaders, paramilitary groups and Marxist insurgencies that negotiated their own precarious peace plans. Yet the overall level of violence, while down significantly from its historic high, continues to be among the highest in the world, and the criminal activities these groups engaged in continue unabated.

Background: The Colombian Emerald Trade

The emerald trade provides an important case study of the multiple players that are involved in the multifaceted violence that has plagued Colombia’s isolated regions and continue to function beyond state control. In particular, these players operate where resource extraction provides a ready source of revenue that can be used to finance private armies and exert political control.

While in recent decades the cocaine trade has been the most lucrative of the illicit economies, over the past five years the illegal mining of commodities has provided similar or greater profits with far less risk. This activity includes the informal gold trade, coltan mining and timber harvesting, all of which operate in similar criminal, non-state ecosystems that have developed over decades and sometimes centuries.

Economic and practical considerations incentivize the rise in black market commodity sales. A recent study noted “cocaine typically takes six months to produce and requires considerable knowledge, while an illegal mining operation in the Colombian jungle can extract two kilograms of gold a week. [Furthermore, a] kilogram of cocaine can sell for about 5 million pesos ($2,570) in the Colombian jungle while a kilogram of gold can fetch 19 times that, or similar to global market prices...The precious metal is also relatively easy to legalize while cocaine remains banned.”[3]

The emerald trade, one of oldest and most violent of these trades, is used as a case study for this paper. The conflict among ideologically diverse actors in a region with little historic state presence, driven by desire to control a valuable natural resource is a long-standing paradigm, and will likely continue to do so for many years.

In keeping with most of Colombia’s extractive industry practices, the Colombian emerald industry has for centuries operated in a vast grey space between the legality and illegality that is the hallmark of territories outside the control of the government. In the emerald trade, quasi-mafia structures dominate the remote mining landscape and where all sides use well-armed paramilitary bands to defend themselves and attack their enemies.

In the Muzo sector of the province of Boyacá, the historically bloody emerald trade is an integral part of the intertwined histories of precious stones, drug trafficking, guerrilla armies, powerful local families that intermarry to bring stability to the trade, and constant betrayals. Knowledgeable sources in the emerald trade say the current low intensity conflict among different factions vying for control of the trade has intensified greatly since the April 2013 death of legendary emerald czar Victor Carranza.

Figure 1: Map of Colombia and Boyacá Province[4]

From the early 1980s until his death by natural causes – after surviving dozens of assassination attempts – Carranza was a key figure in the three epic “Green Wars” that wracked the region, leaving tens of thousands of people dead, as well as a relatively durable truce that halted the widespread bloodshed in the 1990s.[5] In one famous case, when two intermarried clans were having a dispute over a small mining area rich in emeralds, one of the clans turned to Carranza for help because he did not want bloodshed in the family. Carranza reportedly poured cement into the mine tunnels of the other family, killing dozens of workers and took over the entire operation for himself.[6]

While Carranza successfully fought off efforts by Pablo Escobar and the Medellín cartel in the 1980s to control transit routes through the Boyacá region to their strongholds in the Magdalena Medio region, in the end Carranza found that the remoteness of his fiefdom was ideal for establishing his own cocaine laboratories as a complimentary business to gemstones. In addition to his emerald holding Carranza quietly acquired vast tracts of land and armed and fed an army reportedly numbering well over 1,000 soldiers.[7]

As with many extractive industries, the few like Carranza who strike it rich provide hope to the tens of thousands of local miners, known as guaqueros, who hope to get lucky enough to leave the abject poverty in which most of them live. Many of the guaqueros spend much of their lives in narrow, deep underground pits and tunnels that frequently collapse, living a boom and bust cycle depending on what stones they can scratch from the earth.

The Colombian state is virtually absent in the emerald areas, and the main mediators in the long-simmering turf battles are the Catholic priests assigned to region. Due to the military strength of the emerald armies, the FARC never really gained a foothold in the region, although it has operated on the periphery and attempted multiple times to move into the region.

The wars have waxed and waned for decades in part because of a deliberate strategy of emerald bosses of all stripes to keep the main emerald mining areas as physically isolated as possible from the rest of the country – a strategy to evade easy access and control by the central government. Hence, while new roads and airports spring up across the country, the main emerald mining areas, only about 120 miles from the capital, remain accessible only by helicopter or a 6-hour drive in all-terrain vehicles. The vehicles are easy to spot on the isolated roads, where private security forces can stop and turn away anyone’s whose entrance is not authorized.

“The key to the emerald kings surviving is that they still exercise a sort of feudal control over the land and refuse to allow the state to intrude,” said one emerald buyer who has traveled to the mining zone frequently over several decades. “Every major infrastructure project ultimately gets derailed, because if there were highways or airports then the state could come and impose some order. None of the emerald bosses wants that to happen.”

Fears of an impending new explosion of killings in and around the emerald trade have been heightened by the September 2015 announcement by Gemfields Plc, a British-registered company and global industry leader, that it was acquiring a controlling interest of 70 percent in the Coscuez emerald mine. Historically, the mine was one of the world’s richest sources of high quality stones, but production has dropped sharply in recent years.

The group from which Gemfields is acquiring the mine for $15 million, Esmeraldas y Minas de Colombia (Esmeracol), is to remain a minority partner with 30 percent of ownership of the new company being formed with Gemfields, Coscuez NewCo. Both Colombia and the United States law enforcement communities have raised concerns that some of Esmeracol’s largest shareholders have long histories of involvement in the cocaine trade and related money laundering.[8]

Furthermore, the ongoing series of high-profile assassinations of emerald barons, their lawyers and partners seems to be a direct consequence of different groups seeking to fill the leadership void left by Carranza’s death.[9] Now, the fear is that the infusion of new players and new capital into to the volatile Coscuez region will upset the fragile equilibrium among the different power groups that are struggling to preserve a fragile ceasefire.

The high overhead in mining emeralds, its unpredictable yields, and the constant need to navigate the demands of different rival groups - while not sparking mine takeovers by the guaqueros - makes it exceptionally difficult for outside groups to succeed in the trade. In addition, the revenues from Colombia’s emerald exports have fallen from about $480 million a year to about $147 million in 2014,[10] making it even more difficult for industry experts to understand Gemfields’ investment strategy or justification.

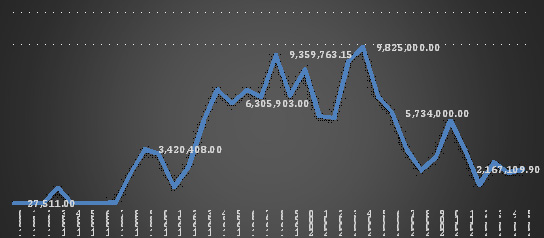

Figure 2: Colombia Emerald Production 1980-2015 (Karats)[11]

“No one in the emerald trade can figure out what Gemfields is doing or why,” said one industry source familiar with the deal. “Outside companies have never survived in the emerald mining fields in Boyacá, and Esmeracol has not relinquished its ties to lots of other dirty businesses. So are they fronting for someone? Are they just naïve? Someone should warn them what they are getting into.”

Another emerald buyer with four decades of experience in the Coscuez mining region who witnessed foreign investors being driven out of the zone through the years, said his advice to investors such as Gemfields would be to, “run. I don’t know who sold them on the idea, but I can guarantee you that it will bring are more trouble than it’s worth.”[12]

Investments like those of Gemfields create a significant dilemma for the Colombian government, which seeks to attract foreign investment to important business opportunities but does not have the resources to adequately monitor the extractive industry. As a result, the government cannot ensure that infusions of investment cash are able to modernize the extractive industries without setting off new resource conflicts, which in turn continue to generate instability. The state must thus determine whether the new investments provide jobs and income in areas of high unemployment and state absence or the money simply serves to strengthen the non-state actors that operate in the region with impunity.

Violence has been hallmark of the emerald trade in the Coscuez sector since at least the Spanish conquest. After decades of inefficient attempts by the state to run a monopoly on purchasing the precious stones, the emerald trade was privatized in the 1970s and slipped further into lawlessness.

Companies like Esmeracol are the most problematic. Esmeracol is deeply tied to the emerald trade, and shareholders have repeatedly appeared as major actors in multiple money laundering and drug trafficking investigations. It is also indicative of how intertwined the multiple conflicts in Colombia are and why they are so difficult to resolve in a way that significantly lowers violence.

Since Carranza’s ascension to the ranks of major emerald kingpins in the 1980s, the emerald trade has been closely linked to cocaine trafficking structures. Carranza and his fellow emerald boss Gilberto Molina were initially happy to sell Pablo Escobar and the Medellín cartel explosives and transit rights through the emerald zone, a key corridor and safe haven beyond state control that linked the cartel’s base in Medellín with the cocaine laboratories and vital trafficking infrastructure in the Magdalena Medio region. For their part, Molina and Carranza also reportedly moved into the cocaine trade in a small way, because they could hide laboratories easily in the remote region and move the product out on roads the government did not control. However, the peaceful coexistence did not last more than a few years.

In the mid 1980s Escobar’s cartel partner Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha (El Mejicano) tried to take over the entire emerald trade by force, in order to create a monopoly in the gemstone trade. The emerald bosses fought back and the ensuing violence was dubbed the first of the modern Green Wars.[13] Rodriguez Gacha killed Molina and 24 of his bodyguards in one battle, and then one of Carranza’s nephews. Carranza was reportedly instrumental in tracking Rodríguez Gacha and providing intelligence so the police could kill him in February 1990. In the end, more than 6,000 people reportedly died in the fighting.[14]

Following Rodríguez Gacha’s death, the Catholic Church mediated a truce among the different emerald groups, and Carranza emerged as the indisputably most powerful figure. Carranza then began expanding his territorial control along major cocaine trafficking routes, reportedly owning more than 1 million hectares (2.5 million acres) of land when he died. The land served as an investment, but also as a crucial safe haven where he could move with impunity.

With the acquisition of land came the expansion of his private military forces to protect his family and his assets, a virtual state within a state. This put him in direct confrontation with the FARC, for whom he had a special dislike. In combatting the FARC his men often operated in tandem or directly with the Colombian army, and his growing political clout at the local and provincial level afforded him multiple guarantees of impunity.[15] Carranza’s elite military units, knows as the Carranzeros, were trained by Israeli mercenaries and were the prototype of the bloody paramilitary armies that emerged a few years later as anti-FARC forces known as the AUC. Underscoring the importance of economics in driving the conflicts it is worth noting that both the FARC and the paramilitary groups that fought them started out with clear ideological foundations then morphed into major drug trafficking cartels over time.[16]

Recent Developments and Ongoing Violence

Many emerald figures followed Carranza’s move into the cocaine trade, intermingling the two worlds where vast amounts of money could be laundered, territory controlled, private armies raised as protection against the state and non-state enemies, and political power amassed.

One of the most notorious cases was that of the leaders of what U.S. law enforcement officials dubbed the El Dorado Cartel, led by Julio Lozano Pirateque, who turned himself into U.S. authorities in Panama in 2010. According to the Colombian attorney general’s office, Lozano Pirateque and his confederates, including major Esmeracol shareholders, had, over the course of the prior decade, sent 900 tons of cocaine to the United States and laundered $10 billion in illicit proceeds through front companies, a professional soccer club, and front men.[17] While Lozano Pirateque did not appear on the corporate registries of Esmeracol, Colombia law enforcement officials and emerald industry insiders said he was one of the most powerful people in the company. Straw purchasers, including family members, held his shares. It was a pattern he and his organization would repeat for many years.

For example, the attorney general’s report says Lozano Pirateque used the Santa Fe soccer club, one of the most popular in the country, to launder hundreds of millions of dollars. In addition, he invested hundreds of millions of dollars in lands and businesses in the names of his children; at the time Lozano turned himself into authorities, his 19-year-old daughter held businesses worth $90 million (according to government records), and her net worth was $250 million.[18]

By 2012 the primary leaders of the El Dorado Cartel were in custody in the United States. These included, in addition to Lozano, Daniel “El Loco” Barrera; Luis “Don Lucho” Caicedo Velandia; and Claudio “El Patrón” Silva Otero. Gen. Oscar Naranjo, head of the Colombian National Police at the time, said the group constituted a “board of directors” of a major cocaine cartel that had close ties to both the Sinaloa Cartel in Mexico and the FARC’s 43rd Front in Colombia.[19]

Another of Lozano Pirateque's Esmeracol collaborators is Jesús Hernando Sánchez Sierra, who holds 54 percent of the shares in Esmeracol and is on the board of directors as of March 20, 2015.[20] Sánchez Sierra was a partner of Carranza in the emerald trade and viewed as one of his likely successors. In 2010 his license to use bodyguards was revoked when authorities found he was illegally deploying the armed men to protect Lozano Pirateque. In October 2012, an assassination team shot Sánchez Sierra nine times as he shopped in a high rent district of Bogotá. Despite losing an eye and a kidney from the attack, he survived and remains active with his company.[21] The assassination was reportedly ordered by Pedro Rincón, known as “Ears” (Orejas), the main competitor of Carranza’s allies in the violent post-Carranza world of gemstones. In response, Carranza loyalists ordered a hit on Rincon’s 17-year-old son, killing him.[22] Rincón was arrested in November 2013 for multiple crimes.[23]

Interwoven with the inter-family violence, often referred to as the “new Green war,” were a series of assassinations of lawyers representing each faction. Lawyers are particularly important because they are link between the illicit holdings of criminal groups and the legal economies into which they put their money. For example, in July 2012, Carranza’s lawyer Mercedes Chaparro Vargas was gunned down in western Boyacá, likely because she managed a mine in which both Carranza and Sánchez Sierra held major shares.[24]

In January 2013, Rincón’s lawyer, Victor Armando Ramírez García, was shot dead in Boyacá’s regional capital of Tunja. An official investigation determined the attack had been ordered by Óscar Murcia, brother of staunch Carranza ally Luis Murcia, in collusion with the Urabeños, a criminal group. [25] Six months later, in June 2013, another Carranza lawyer, Óscar Casas, was shot dead in Bogotá; days later, a local councilman who had been close to Carranza was killed in Boyacá. [26]

While high-profile assassinations have continued, perhaps the most important was the May 2014 assassination of Pedro Alejandro Rojas, AKA “Martín Rojas,” a prominent emerald dealer and, like Sánchez Sierra, a shareholder in Esmeracol. He was killed as he left a cockfight in downtown Bogotá, and was one of the last of the old guard emerald dealers who had worked directly with Carranza and the truce of the 1990s.[27]

Learning from the Emerald Trade: Lessons for the FARC Peace Process

This overview, which is far from a detailed rendering of the alliances and violence that have made the emerald trade a point of convergence for multiple criminal organizations, illustrates how difficult and costly the process of reasserting state control over geographic space controlled by violent non-state actors can be.

To its credit, successive administrations in Colombia, with significant U.S. support and engagement, have tried to implement costly, long-term projects to try to address the deep structural issues that have driven Colombia’s multiple and cross cutting conflicts.[28] Given the FARC’s size, territorial control, and deep involvement in the cocaine trade and other criminal activity, reaching a formal peace process is an important step in this effort.

However, there are several key lessons to be drawn from other conflicts that must be incorporated as the FARC peace process moves forward. As the emerald trade and other conflicts have shown, formal agreements often mean little without strict monitoring of compliance on all sides, and removing key leaders or structures often serves to atomize the conflict rather than resolve it. When Pablo Escobar and other leaders of the Medellín cartel were killed and the Cali cartel leader jailed, cocaine continued to flow unabated; when the EPL demobilized in 1991, a core group of several hundred combatants simply kept their weapons and emerged as a major criminal group that exists to this day.

When Carranza died, the conflicts in the emerald region intensified. The formal surrender and demobilization of the AUC gave birth to multiple criminal organizations that now control at least as much territory and criminal activity as their paramilitary forerunners did.

Given this history, it would be unwise to assume that, even if the FARC leadership were genuinely interested in peace (an assumption shared by few who know the FARC well), all factions of the FARC will truly demobilize and not continue to be well armed, well trained guns for hire or form new criminal groups.[29]

The emerald trade also shows that most conflicts spread beyond competition for the core commodity (political power, economic power, or control of extractive industries) that sparks the violence. Over time, the emerald wars spread beyond gemstones to land conflicts, community violence, and disputes over cocaine production and routes. Emerald barons also demonstrate that the real prize for most groups is political control at the local and provincial levels; this control serves to guarantee both impunity and territorial control, as well as feed the egos of those who seek political legitimacy for their criminal activities.

The acquisition of local political control will likely to be a main focus of the FARC and whatever groups arise from the FARC in a peace process. Territorial control and the loyalty of the communities will be paramount as the FARC and others seek to gain political legitimacy, control key territory, remain shielded from prosecution for crimes of the past, and retain impunity for ongoing criminal activities.

With or without the FARC, festering conflicts like the emerald wars will continue to deprive the Colombian state of legitimacy, revenues and territorial control, while its citizens who live in those areas are denied their basic right to live in a secure peace with political and economic freedom. Removing the FARC from the battlefield an important first step on a long road to peace and prosperity in Colombia.

End Notes

[1] For a detailed history of Los Urabeños and the ties to AUC see: Jeremy McDermott, “The Evolution of the Urabeños,” InSight Crime, May 2, 2014, accessed at: http://www.insightcrime.org/investigations/the-evolution-of-the-urabenos

[2] For a closer look at the Megateo structure see: “Victor Navarro, alias ‘Megateo,’” InSight Crime, November 17, 2016, accessed at: http://www.insightcrime.org/colombia-organized-crime-news/megateo-epl

[3] Andrew Willis, “Gold Beats Cocaine As Colombia Rebel Money Maker: Police,” Bloomberg News, June 21, 2013, accessed at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-06-21/gold-beats-cocaine-as-colombia-rebel-money-maker-police and: Andrew Willis and Michel Smith, “Colombia Illegal Gold Mines Prosper in Global Rout,” Bloomberg News, July 24, 2014, accessed at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-07-24/colombia-illegal-gold-mines-prosper-in-global-rout and http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/ML-TF-risks-vulnerabilities-associated-with-gold.pdf

[4] Source: Official site of Mayor of Cucaita, Boyocá, Colombia. Accessed December 4, 2016 at: http://www.cucaita-boyaca.gov.co/mapas_municipio.shtml?apc=bcEl%20municipio%20en%20el%20pa%EDs-1-&x=2942776.

[5] Steven Dudley, “How Colombia’s Emerald Czar Outsmarted the Law,” InSight Crime, April 5, 2013, accessed at: http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/how-colombias-emerald-czar-outsmarted-law

[6] Author interview with emerald merchant with direct knowledge of events, September 2016.

[7] Dudley, op cit.

[8] Details of the acquisition were made public in a notice published by the news service of the London Stock Exchange: Regulatory Story, “Gemfields plc, Acquisition of controlling interest in two emerald projects in Colombia,” RNS Number 6369Y, September 10, 2015, accessed at: http://www.londonstockexchange.com/exchange/news/market-news/market-news-detail/GEM/12494673.html

[9] For some details of the post-Carranza conflicts see: Kyra Gurney, “Colombia’s ‘Green War’ Reignites with Death of Emerald Baron?” InSight Crime, September 15, 2014, accessed at: http://www.insightcrime.org/news-briefs/emerald-war-colombia-luis-murcia

[10] Eugen Iladi, “The dark side of gem stones in Colombia and beyond,” Colombia Reports, July 26, 2016, accessed at: http://colombiareports.com/dark-side-gem-stones-colombia-beyond/

[11] Graphic created from data listed at the following source: SIMCO (Sistema de Información Minero Colombiano), “HISTÓRICO PRODUCCIÓN DE ESMERALDAS, 12/31/1940 hasta 12/31/2015.” Accessed October 6, 2016 at: http://www.upme.gov.co/generadorconsultas/Consulta_Series.aspx?idModulo=4&tipoSerie=113&grupo=350

[12] Author interviews in Colombia, September 2016. For an interesting look at one foreign company’s ongoing troubles in the post-Carranza era see: Joshua Paltrow and Julia Symmes Cobb, “The Dangerous Search for Emeralds in Colombia,” The Washington Post, August 9, 2015, accessed at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/world/2015/08/09/the-dangerous-search-for-emeralds-in-colombia/

[13] See: Dudley, op cit.

[14] “Victor Carranza: el intocable,” Revista Semana, June 4, 2013, accessed at: http://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/victor-carranza-intocable/338973-3

[15] Dudley, op. cit.

[16] “Victor Carranza: el intocable,” op. cit.

[17] Redacción Judicial, “Dineros ilícitos ingresaron a Santa Fe hace ocho años,” El Espectador, October 6, 2010, accessed at: http://www.elespectador.com/noticias/judicial/dineros-ilicitos-ingresaron-santa-fe-hace-ocho-anos-articulo-228293

[18] Redacción Judicial, op cit.

[19] Elyssa Pachico, “Financial Head of Colombia ‘Soccer Cartel’ Arrested,” InSight Crime, April 28, 2011, accessed at: http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/financial-head-of-colombia-soccer-cartel-arrested. See also: United States v. Caicedo Velandia et al, United States District Court, Eastern District of New York, June 7, 2010. It appears from court records that all four men struck deals with the U.S. attorney, possibly in exchange for high value information of the Mexican cartels they dealt with and the FARC. Transcripts for the sentencing of Lozano are also not publicly available, which is unusual unless the person turned state witness. In addition, all received sentences of less than 10 years in prison, which are extremely light given the magnitude of the crimes they committed.

[20] Unidad Investigativa, “Los nuevos ‘zares’ de las esmeraldas,” El Tiempo, May 19, 2013, accessed at: http://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-12809002

[21] “Esmeraldero baleado en zona T era socio de Carranza,” Confidencial Colombia, October 9, 2012, accessed at: http://confidencialcolombia.com/es/1/203/2651/Esmeraldero-baleado-en-zona-T-era-socio-de-Carranza-balacera-zona-t-centro-comercial-esmeraldas.htm

[22] Pacho Escobar, “La tragedia del esmerladero Pedro Nel Rincón, alias ‘Pedro Orejas,’” Las 2 Oriillas, January 26, 2014, accessed at: http://www.las2orillas.co/la-tragedia-de-pedro-nel-rincon/

[23] “Detenido el esmeraldero ‘Pedro Orejas’ por presunto concierto para delinquir,” Colprensa, November 20, 2013, accessed at: www.elpais.com.co/elpais/judicial/noticias/detenido-pedro-orejas-por-presunto-delito-concierto-para-delinquir

[24] Redacción Boyacá, “Repudio en Boyacá por asesinato del líder cívica y activista de la paz,” El Tiempo, July 4, 2012, accessed at: http://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-11997474

[25] Redacción Judicial, “Las pruebas que comprometen al clan esmeraldero Murcia con ‘Urabeños,’” El Tiempo, April 8, 2014, accessed at: http://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-13798279

[26] Redacción Boyacá, “Atentado a ‘Pedro Orejas’ revive fantasma de la ‘guerra verde,’” El Tiempo, November 11, 2013, accessed at: http://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-13176195

[27] Unidad Investigativa, “Crimen en galería, una advertencia al grupo de Carranza,” El Tiempo, May 17, 2014, accessed at: http://www.eltiempo.com/politica/justicia/crimen-en-gallera-una-advertencia-al-grupo-de-carranza/14002421

[28] For an overview of these programs see: Carl Meacham, Douglas Farah, Robert Lamb, “Colombia: Peace and Stability in the Post Conflict Era,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, D.C., March 2014, accessed at: https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/140304_Meacham_Colombia_Web.pdf

[29] For a more complete look at the future of the FARC’s criminal activities see: Jeremy McDermott, “Criminalization of FARC Elements Inevitable,” InSight Crime, May 21, 2013, accessed at: http://www.insightcrime.org/investigations/future-farc-after-peace