Business, Crime, or Crazy: Toward Understanding Mexican Drug Trafficking Organizations’ Rationality

Timothy Clark

Introduction

There is disagreement on the basic nature of Mexican drug trafficking organizations (DTOs). In the Mexican press, the prevailing narrative on DTOs is one of irrational actors committing indiscriminate violence (Housworth 2011). Meanwhile, recent U.S. media reports and academic scholarship have characterized Mexican-based DTOs as rational actors who make business decisions and are concerned with maximizing profits. For example, the New York Times 2012 series Cocaine Incorporated described

the primal horror of Mexico’s murder epidemic makes it difficult, perhaps even distasteful, to construe the cartel’s butchery as a rational advancement of coherent business aims. But the reality is that in a multibillion-dollar industry in which there is no recourse to legally enforceable contracts, some degree of violence may be inevitable (p. 1).

Furthermore, Manwaring (2007) argues that modern Mexican DTOs, that he classified as third-generation street gangs, are motivated by an entrepreneurial mindset. In this mindset the DTOs conduct actions to control illicit commercial markets.

While these latter sources characterize DTOs as rational, there has only been very limited research to assess the rationality of DTOs (Dell 2011, Masucci 2013, Widner et al. 2011). Moreover, rationality also implies that deterrence will stop these crimes. Despite this lack of systematic assessment, policy makers, law enforcement practioneers and planners oftentimes speak of deterring DTOs by making the price too high to transport drugs. For example, Brooking Institute scholar Vanda Felbab-Brown in her 2014 assessment of Mexican policy discussed solutions in terms of increasing Mexican capacity of deter crimes around drug trafficking. Moreover, during the administration of Mexican President Felipe Calderon (2006-2012), the central goal of Mexican drug policy was increasing the DTOs’ costs of doing business (Guerrero-Guttierez 2011, Shirk 2011). However, for deterrence to be effective, it requires actors to use rational decision-making processes where they weigh the potential costs against the possible rewards of a behavior.

This current study adds to the limited research on DTO rationality by systematically assessing DTOs’ actions. By focusing on specific actions taken by Mexican DTOs between the years 2011-2012, and assessing the rationality of these actions, this study gives policy makers, law enforcement practioneers and planners another reference point to understand the degree and nature of these criminal organizations’ rationality.

Previous Research on Drug Trafficking Organizations and Rationality

Research on DTO rationality is limited. This research has focused on macro-level processes of the rational motivations of the populace for being involved in drug trafficking related crime (Masucci 2013; Widner et al. 2011), or rationality in DTOs’ route selection as related to general deterrence (Dell 2011).

Widner et al. (2011) tested an economic theory of human behavior as applied to Mexican drug trafficking and related crime. They derived their theory from Becker (1968) who posits an individual decides to commit a crime when the individual’s expected benefit from committing a crime exceeds the individual’s risk. This theory considers

the lower the costs and higher the benefit of committing a crime, the more motivated an individual is to be a delinquent. In a system where the probability of getting caught and punished when committing a crime is low, the propensity for crime is high (Widner et al., p. 604).

Widner et al. (2011) base their analysis of individuals’ involvement in DTOs on the premise that improvements in legitimate labor market opportunities make crime relatively less attractive while worsening economic conditions make crime more attractive to potential criminals. Additionally, they hypothesized that

when more is spent on public security and there is a greater police presence, the probability of getting caught committing a crime increases and the expected cost of committing a crime increases. Fewer crimes should be committed (p. 607).

In their analysis of Mexican communities, they found support for this deterrence model as higher incarceration rates had a significant effect in decreasing the number of arrests for all types of crime. They found more resources devoted to prisons and incarceration could have a significant effect on crime in Mexico by taking criminals off the street and raising the cost of committing crimes to would-be criminals appears to be working.

Masucci (2013) also attempted to quantitatively test a rational choice model of participation in Mexican drug trafficking. To accomplish this test, Masucci analyzed the growth of the drug trade and drug-related violence though focus on economic conditions in urban areas along the US/Mexico border during the administration of Mexican President Calderon (2006 to 2012). Masucci hypothesized drug activity is a rational adaptation by an economically disadvantaged population. Mascucci operationalized this behavior as municipal-level economic indicators, homicides and drug arrests. Masucci’s analysis found no support for a rational choice explanation of why the populace engaged in drug trafficking as there were no strong correlations between these economic indicators, homicides, and drug arrests.

While Widner et al. (2011) and Macussi (2013) focused on rational actions of members of the Mexican populace being involved in drug trafficking, Dell (2011) looked at the DTO itself as an actor and focused on the DTOs’ route selection as an indicator of rationality. Using data from 2007 to 2009, Dell analyzed municipalities where Mexican security forces’ anti-DTO activity was more severe. She assumed municipalities where mayors are more closely associated with the ruling National Action Party’s (PAN) forceful security agenda would be more costly for DTOs to operate within. Using this variation in hostility toward DTOs, Dell modelled the changes in trafficking routes that DTOs adopted in response to this variable hostility. Dell (2011) used two network models of drug trafficking in her analysis. The first model specifies “the trafficker’s objective is to minimize the costs incurred in trafficking drugs from producing in municipalities across the Mexican road network into the United States.” (p. 66). Dell assumed it is more costly to traffic through more heavily enforced municipalities (i.e. those ran by PAN politicians). Dell also estimated a second more-complex model which imposed congestion costs when trafficking routes coincided. For both models, Dell found that in PAN controlled areas, where Mexican security forces increased their presence and cracked down on drug trafficking, the DTOs responded by diverting their trafficking networks in predictable ways. Thus, Dell found the DTOs shifted trafficking routes to avoid municipalities where crackdowns were occurring thereby supporting a rational model of DTO activity.

Dell’s work has drawn attention among commentators of the Mexican drug war. For example, Housworth (2011), a risk consultant and occasional writer for the on-line drug-war-focused news site Borderland Beat, supports Dell’s conclusions. According to Housworth,

though notorious for their brutality, Mexico’s organized criminal groups are rational actors who respond to market dynamics. If they are not forced into a showdown or loss of face, their behavior can be influenced (page 1).

Housworth constructs a theoretical model by drawing parallels between Mexican DTOs behavior to his previous (2008) research findings on African “Blood Diamond” warlords’ behavior. Housworth argues that these geographically separated groups “share motives, methods, ferocity and absence of restraint. Both cartels and warlords are attempting to extract wealth from areas under their control while repelling competitors” (p. 1). Housworth points to the diversification of DTOs in the face of increased security force enforcement pressure under the Mexico’s Calderon and following September 11, 2001 in the United States, as an indicator.

On the other hand, Ramsey (2011), an analyst for Insight Crime, critiqued Dell’s (2011) work as overstating rationality of DTOs. Ramsey argues

that the nature of the world market for illicit drugs ensures that the profit motive is behind much of drug trafficking organizations’ behavior, but it is important to remember that they are also influenced by a myriad of other factors which do not easily translate into cost-benefit calculations (p. 1).

As evidence, Ramsey cites anecdotal evidence of murders of U.S. citizens in Mexico and massacres committed by Mexican DTOs that attract police attention and lead to crackdowns on DTO activity. Moreover, Ramsey cited the cartels “tendency to divide and divide again,” thereby weakening themselves, as further examples of irrationality (p. 1).

Thus, this previous literature is divided on their views of the level and nature of Mexican DTO rationality. This debate serves as a frame for this current analysis that will empirically determine the degree that Mexican DTOs act rationally.

Rationality Operationalized

First, we must consider rationality. In considering claims of DTO rationality, it is useful to differentiate between two types of rational action—business rational action and criminal rational action. First, business rational actions are actions that legitimate businesses use to maximize profits. Coase’s (1937) Theory of the Firm defined rationality as tied to near and long-term profit. According to Hart (1989), the Theory of the Firm describes that the theory:

views the firm as a set of feasible production plans. A manager presides over his production set, buying and selling inputs and outputs in a spot market and choosing the plan that maximizes owner’s welfare. Welfare is usually presented by profit, or, if profit is uncertain so that profit-maximization is not well defined, by expected net present value of future profit (possibly discounted by risk) or by market value (p. 175)

Thus, business rational actions are parts of feasible production plans and those actions that maximize profit or expected profit. These are actions such mergers, alliances, cooperation with other complimentary businesses and producers, diversification, and market forecasting.

Some examples of DTOs’ being business rational would be mirroring these practices of legal business organizations to maximize profit or expected profit. They would seek alliances and merge with other DTOs as a means to gain strength and capture control of the market. They also would cooperate with other DTOs to move illicit drugs with some DTOs controlling the production cooperating with other DTOs which transport and distribution of the drugs. Additionally, DTOs would diversify into other commodities, both licit and illicit. They also would demonstrate expertise in market forecasting assessing the amount of illicit products that consumers will use in a given region and adjust their logistics and production accordingly.

The second type of rational DTO actions is those actions that seek to maximize profits for the organization but are illegal and out of bounds for legal business. These would include behavior such as assassination of rivals, and mass murder to display power. While criminal, these actions would not be irrational for DTOs. This is similar to Housworth’s (2011) argument that “criminal actions that appear irrational to the public generally have very sound operational and profit-driven motives” (p. 2). Similarly for DTOs, Widner et al. (2011) believed

in the case of homicide involving drug activity, the benefit to the murderer may be the elimination of a rival. Alternatively, the benefit to the murderer or hit man may be cash from the cartel. If the expected cost to the hit man is relatively low such as the case when the probability of being caught is low or when there are few labor market opportunities available, more homicides would be expected (p. 606).

Considering this distinction between business rationality and criminal rationality, we can then categorize DTO irrational behavior. Irrational behavior is any action that does not fit into the either of these two other types of actions and incurs a cost without benefit. In essence, irrational action will be identified as any action that puts the drug trafficking organization at risk without any gains, either in profit or power relations. Thus armed with these three operationalizations of DTO actions (business rational, criminal rational, and irrational), we developed an analysis to assess DTO rationality, and sources of possible variation in the occurrence of irrationality, and business and criminal rationality.

Methods

Wider et al.’s (2011), Masucci’s (2013), and Dell’s (2011) analyses of DTO actions are informative, but they attempt to understand micro-level processes, in this case decision-making, with macro-level views of social behavior—drug routes, community-level economic and social variables. This is similar to the fallacy that Simon (1978) describes when economists’ tested of the theory of the firm as they “erroneously supposed that microeconomic theory can only be tested by its predictions of aggregate phenomena” (p. 347). Simon argued that instead testing at the micro-level promised more accurate insights into the decision-making processes.

In defense of Widner, Masucci, and Dell, research at truly micro-level decision-making practices of DTOs (i.e. how decisions are made within the organization) have not yet been conducted due to criminal, clandestine, and dangerous in nature of face-to-face research on the Mexican drug trade. Likewise, this truly micro-level analysis of DTO decision-making is beyond the scope of this current study. However, this current study will take us a step closer, down from macro-level view to a studying of the DTO’s actions at the event-level of analysis.

This current study analyzes all Mexican DTO actions reported in a dataset by the Institute of Study of Violent Groups (ISVG). For this database, the ISVG used native-born Spanish-English bilingual speakers to review Mexican and U.S. newspapers’ reporting on DTOs and violence across the U.S. and Mexico between 2011 and 2012. These reviewers recorded and translated all articles creating a dataset of over 2,000 articles. Using this dataset, this current study extracted those articles that specifically mentioned Mexican DTOs (either by specific name or more generally, i.e. drug cartel), and included a connection to a verb. The verbs were then coded to identify the level of rationality using the schema discussed previously—business rational, criminal rational, and irrational—to create an event-level dependent variable by which this current study explores the degree and nature of DTO rationality.

Independent Variables

This current study analyzes variation in this event-level dependent variables of DTO rationality using independent variables of geographic area, specific DTO culture, the level of the actor within the DTO (corporate aggregate, small-group, or individual), and the interaction-effect of level of actor by specific DTO. In doing so, the analysis will explore possible variation in the occurrence of DTO irrational and rational actions (both business and criminal in nature).

Regional Variation

One independent variable is regional variation. For this analysis the regions were categorized as: U.S. Border States; Canada and non-U.S. Border States; northern Mexico; central and southern Mexico; Central and South America; and areas other than the Americas.

In 2011 and 2012, those U.S. states nearest to the US-Mexico Border (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas) were the frontlines for the drug interdictions. These two years were peak years in this region for border enforcement with expenditures of 18 billion dollars and employed over 45,000 Agents (Custom and Border Protection Officers, Border Patrol Agents, Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agents) (Immigration Policy Center 2014). During the same period, these agencies, coupled with local, state, and other federal agencies (such as Federal Bureau of Investigation, Bureau of Achohol, Tobacco and Firearms, and Drug Enforcement Agency) were experimenting with a variety to configurations for joint operations such as High-Intensity Drug High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA), Federal and State Fusion Centers, Border Enforcement Security Task Forces (BEST), and Unified Commands (Bjelopera and Finklea 2014). These U.S. law enforcement agencies, individually or jointly, manned a gauntlet of ports of entry, border fences, border monitoring efforts, patrols, surveillance, and inland border checkpoints that offered the best chances for interdiction. These measures forced DTOs to use a variety of time-honored and innovation trafficking techniques to cross these states. Thus, for DTOs these areas were fraught with dangers from U.S. federal, state, and local law enforcement efforts to disrupt the flow of drugs northward, and the flow of money and weapons southward.

Farther north, the U.S. non-Southwest Border States and Canada were the destination zones for tons of drugs, and the homes of millions of the DTOs’ customers (Flener 2011). This geography provided a wide and diverse landscape for DTOs to operate acting in conjunctions with allied U.S. and Canadian-based gangs. In 2011 and 2012, while law enforcement were involved in numerous local, state, and interstate efforts, DTOs continued to successfully move drugs into urban and rural areas. While the bulk of the drugs were marijuana, these DTOs’ efforts included diversification into methamphetamine and heroin.

Just as the US Border States were key zone for trafficking, the Mexican states along the Mexican northern border were also key to the drug trade. DTO strongly sought after these “plaza” areas that served as key staging areas for drugs and immigrants Northward, and gathering points for weapons and bulk cash into Mexico (Lee 2014). Masucci (2013) observed that DTOs had infiltrated the local and state Mexican police in the region greatly reducing the probability of DTOs getting caught. More precisely, local Mexican police officers were outgunned and forced to comply with, and even assist the DTOs. These police officer and police departments were given a choice of plata o plomo (silver or lead)—taking a bribe or being killed. This lack effective guardianship provided a low chance of the DTOs getting caught by Mexican local and state police. Despite corruption in the police forces, from 2008 to 2012 these areas were the battlefields that Mexican President Calderon deployed tens of thousands of Mexican soldiers, Marines, and federal police engaged in widespread use of force, and at times violating human rights, to arrest or destroy entrenched DTOs (Lee 2014). Meanwhile DTOs took advantage of competitors weakened by these federal efforts and used violence to gain an advantage and gain control of the valuable plazas such as Tijuana, Mexicali, Nogales, Ciudad Juarez, Nuevo Laredo, and Reynosa. Overall these areas became dangerous areas for DTOs to hold and acquire due to threats from the Mexican military and other DTOs resulting in DTOs’ use of widespread and brutal violence, torture, and intimidation.

Meanwhile, central and southern Mexico in 2011and 2012 were stable relative to the Northern Mexican Border States (Lee 2014). DTOs in this region had historic trafficking networks that collaborated with other DTOs, and clashes with Mexican security forces were minimized allowing the DTOs in some areas to operate with near impunity when transporting drugs to the northern Border States. Moreover, DTOs in southern Mexican states, like Jalisco, Michoacan, and Guerrero, DTOs were oftentimes tied to indigenous peoples and villages where the DTOs served as self-help groups by protecting and providing for the populace (Beittel 2013). This created a supportive populace that assisted DTOs in concealment of trafficking, and alerted DTOs of outsiders or security forces.

For Central and South America during this period, Mexican DTOs used a mixed method for establishing themselves that varied by DTO. Los Zetas in Guatemala entered aggressively threatening and violently confronting local DTOs and security forces, while Sinaloa Cartel tried to work cooperatively with local DTOs and gangs (Grayson 2013). Meanwhile, during this period Mexican DTOS were trying to establish networks in areas outside of the western hemisphere (such as in Europe, Southeast Asia, and North and East Africa) (Diaz De Mera 2012). In these areas Mexican DTOs kept a relatively low profile established working partnerships with local and regional DTOs.

DTO Cultures

While these different geographic areas may have produced different levels of rationality in DTOs’ behavior, scholars have noted that differing organizations exhibit different levels of rationality based upon their organizational culture (Linnenluecke et al. 2009, Sackmann 1992). Moreover, criminologists have long noted that criminal subcultures have an effect on organizations’ level of rationality (e.g., Marongiu, and Clarke 1993, Simpson et al. 2002, Cornish and Clarke 2002). Thus, another possible variation for DTO rationality would be across the organizational cultures of specific DTOs. Relevant for this current study are the organizational cultures for the following DTOs appearing in the ISVG dataset: La Familia Michoacana, Knights Templar, Sinaloa Cartel, Gulf Cartel, Los Zetas, Arellano Felix Organization , Juarez Cartel, and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel.

La Familia Michoacana (LFM) started in the 1980s as a vigilante group to eradicate drug use in the southwestern state of Michoacán (Beittel 2013). In 2011 and 2012, it was still based in the state of Michoácan but its operations stretched up into the Mexican northern Border States. These operations specialized in methamphetamine production but also trafficking marijuana, cocaine, and heroin. During recruitment, LFM emphasized religion and family values, and claimed that they were for the commoners (la gente). They donated food, medical care, and schools to benefit the poor in order to project a “Robin Hood” image (Beittel 2013, p. 10). They were reported to also not allow their members to sell methamphetamine to locals and often placed narcobanners in town squares denouncing intolerance for drug abuse and violence against women and children. However, they also engaged very brutal attacks on Mexican security forces and rival DTOs which they labeled as “divine justice.” (De Amicis, 2010).

In early 2011, a new organization operating in the state of Michoacán emerged out of the LFM calling itself the Knights Templar (Los Caballeros Templarios--LCT) led by the charismatic former LFM lieutenant, Servando Gomez (alias “La Tuta”)” (Beittel 2013, p. 18). LCT saw themselves modeled after historic crusading European knights vowing to protect the people of Michoacán from other DTOs and alleged persecution by the Mexican government. They claimed adherence to a code of conduct that was published in a 22-page booklet that describes the group as defending the morality and values of Michoacana people.

Meanwhile, the Sinaloa Cartel had its origins in the 1960s and 1970s as small groups of rural families living in the state of Sinaloa cooperated to move contraband, primarily locally grown marijuana, into the United States. Insight Crime (2015) describes the Sinaloa Cartel as “more like a federation than a tightly knit organization” and not completely hierarchical with three leaders (El Chapo, El Azul and El Mayo) maintaining their own separate but cooperating organizations (p.1). The DTO’s decentralized structure of loosely linked smaller organizations made it susceptible to internal conflict when units broke away. At the same time, the decentralized structure enabled it to be quite adaptable in the highly competitive and unstable environment that prevailed in 2011 and 2012 (Beittel 2013). Part of their adaptability was successfully penetrating government and security forces wherever the DTO operated and often opted for the bribes over the bullets, and alliances over fighting (Insight Crime, 2015). However, when cooption failed, the DTO readily used violence.

Meanwhile, in contrast to the Sinaloa Cartel that preferred a culture of cooperation and cooptation, the Gulf Cartel sought to maintains its control of northeastern states of Mexico through excessive violence and intimidation. Based in the border city of Matamoros in the northeastern Mexican state of Tamaulipas, the Gulf Cartel arose in the bootlegging era of the 1920s (Beittel 2013). By the 1980s, the DTO developed ties to the Mexican Federal Police and the Colombia’s Cali cartel, and even corrupted an elite Mexican military force that became known as Los Zetas and fused with the Gulf Cartel. Since 2007, the Gulf Cartel has experienced a loss of multiple leaders to successful law enforcement operations and internal struggles, but continued to successfully move drugs. In 2011 and 2012, the DTO was in a desperate battle with Los Zetas cartel for control over the Gulf Cartel’s former strongholds in Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, and Veracruz. In 2012, multiple factions of the DTO competed to reunify the organization under a single leadership but were not successful. As result of these conflicts, the Gulf Cartel went from being one of the most powerful Mexican DTOs in 2007, to having its area of influence greatly diminished by 2012.

When Los Zetas split from the Gulf Cartel in the period of late 2008 to 2010, it became an independent DTO (Beittel 2013). Consistent with their origins as an elite security force of 30 deserters from the Mexican Military, Groupo Aeromovil de Fuerzas Especiales (GAFES), Los Zetas were known for strong show of force and violent urban warfare tactics such as commando-style raids on state prisons, abduction of journalists, murder of police, and attacks on military posts (De Amicis 2010, Beittel 2013). The DTO diversified into criminal activities including ransoming, weapons smuggling, extortion, and non-drug illicit smuggling, such as knock-off goods and stolen fuel.

In addition to LFM, the Gulf Cartel, and Los Zetas DTOs, this current study considers the culture of the Arellano Felix Organization DTO, also known as the Tijuana Cartel. Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo, a former police officer from Sinaloa who is considered as “one of the founders of modern Mexican DTOs” created a network called La Alianza de Sangre (The Alliance of Blood). This alliance included the Arellano Felix family, and numerous other DTO leaders such as Amado Carrillo Fuentes, Rafael Caro Quintero, and Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán” (Beittel 2013 p. 10, Smith 2012b). In late 1980s, Felix Gallardo (AKA: “El Padrino” or the Godfather) divided trafficking routes among the members of his organization (Vazquez del Mercado, 2012). What is now known as the Arellano Felix Organization resulted when Gallardo assigned the border city of Tijuana in Baja California to his nephews, the Arellano Felix brothers Benjamin, Ramon, Francisco Javier, Rafael, Eduardo, and his niece, Enedina. The Arellano Felix Organization is the most family centered of all drug trafficking organizations in Mexico since its leadership has never been outside of the Arellano Felix family. Under Ramón’s brutal enforcement methods and Benjamin’s leadership, this organization grew to be one of the most important DTOs in the 1990s and early part of the 2000s. By 2011 and 2012, the DTO was involved in drug trafficking, retail illegal drug sales in Mexico, extortion, kidnapping and human trafficking. Additionally, it had organized cocaine smuggling routes from Colombia through Central America and Mexico as well as smuggling marijuana from Mexico into the United States. The DTO is recognized for its innovative culture that has included using fake law enforcement vehicles and uniforms to conceal their movements, torture, and other extreme violent methods to kill members of rival DTOs.

Meanwhile, the Juarez Cartel was formed in Ciudad Juarez during the late 1980s by Rafael Aguilar Guajardo—a former Mexican intelligence officer (Smith 2012b). Under Guajardo, the Juarez Cartel became one of the largest trafficking organizations in Mexico establishing control of key narco-trafficking routes into the United States from Ciudad Juarez and participating in drug and human trafficking, kidnapping, and protection rackets. The DTO moved large amounts of marijuana, cocaine, and MDMA across the border to groups distributing in U.S. markets (Smith 2012b). By 2011, the Cartel had two separate enforcer arms. La Linea that was made up of current and former police and military operatives and the Barrio Azteca gang that operated in both Ciudad Juarez and the United States. During this period, they used extreme and excessive displays of violence in waging war against Mexican police forces and rival DTOs including employing improvised explosives devices. Since 2004, the Juárez Cartel has been viciously engaged in a fight with the Sinaloa Cartel to maintain their core territory around Ciudad Juárez (Beittel 2013, p. 12). This conflict resulted in thousands of deaths in Ciudad Juárez, making the surrounding Mexican state of Chihuahua the deadliest in the country. As a result of the conflict with the Sinaloa Cartel, by the end of 2012 the Juarez Cartel was weak and losing ground to Sinaloa Cartel, Los Zetas, and the LFM.

The final DTO found in the IVSG dataset was the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). This DTO is regional in scope across Jalisco, Michoacan, Nayarit, Colima and Guerrero (Perez Caballero 2014). The DTO formed in July of 2010 after the death of Juan Ignacio Coronel Villarreal who controlled the now defunct DTO known as the Milenio Cartel—a part of the Sinaloa Cartel (Smith 2012a). After his death, members of his group still loyal to Sinaloa formed the organization now known as La Resistencia while other defected to form the Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generacion (CJNG). In 2001 and 2012, the CJNG waged a turf war against La Resistencia, LFM, and the Sinaloa Cartel for control of the drugs running through Jalisco as well as for control of precursor chemicals arriving from Asia. The DTO adopted localized strategies that showed in-depth political understanding and sophisticated information operations. For example, in some areas the CJNG directly attacked the Mexican Army, but in Michoacan it sought alliances with the Mexican security forces. They even intervened in the conflict between the self-defense groups and the Knights Templar by infiltrating the Knights in order to weaken the DTO and help the authorities and the self-defense groups (Perez Caballero 2014). In another example, the CJNG temporarily in Veracruz renamed their local members as the Mata Zetas (Zeta-Killers) and struck surgically against Los Zetas where they were weakest. Afterwards CJNG eliminated the name and dismantled the force (Perez Caballero 2014).

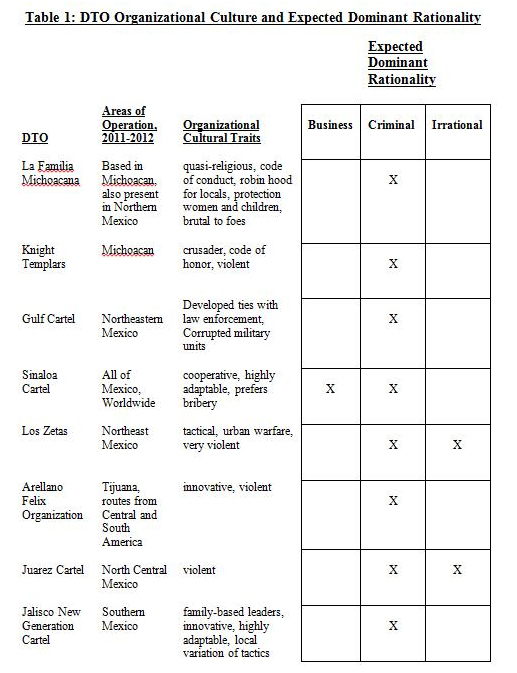

Table 1: DTO Organizational Culture and Expected Dominant Rationality

Overall, Mexican DTOs differ along a variety of cultural factors (see table one). These cultural factors vary from quasi-military organizations, to self-conceptualized Robin Hood-like protectors of locals and crusaders, and to business-minded alliances. Moreover, these different DTO-specific cultures have different techniques, tactics and practices that they prefer ranging from innovation, cooperation, to bribery, intimidation, and to excessive displays of violence. With these insights, this study will treat the culture of each specific-DTO as a possible source of variation in level of DTO rationality.

Level of Actor

Ramsey (2011) argues that researchers, such as Dell (2011), have treated DTOs like relatively cohesive actors similar to rival sports teams or corporations. Ramsey argues that relations between “local cells of cartels are much more likely to vary according to complex regional identities and variations in the strength of the chain of command” (p. 1). Simpson et al. (2002) identified this as part of a “collectivity problem” within rational choice theory which could be solved by considering the behavior of the corporation aggregates, subgroups, and individuals within the corporation as actors (p. 32). This current study draws upon Simpson et al.’s and Ramsey’s insights, and analyzes specific DTO variation in rationality by different level of actors. This current study uses an independent variable that differentiates between the level of actors: individual action, small group action, and corporate aggregate action. These level of actors are operationalized as follows:

- Individual action is tied to a specific individual, i.e., an assassin was arrested for disposing of bodies in chemical vats; another trafficker displayed personalized license plates that read “Narco”). This may include a DTO leader if the action is personal and not carried out by the DTO collectively (i.e., DTO leader is living in smaller less extravagant homes to avoid detection).

- Small group action is carried out by a small group of DTO members that does not appear to be repeated over and over by multiple groups within a DTO (i.e., killing a certain law enforcement officer, group of five men getting caught transporting a load of drugs). This also includes action by a subgroup of a DTO against other subgroups within the DTO (i.e., cells within the DTO are fighting one another for control of an area). This also includes activity that could be conducted by a subgroup of the cartel without support of the DTO (i.e., detonate a car bomb despite leadership approval).

- Corporate aggregate action is activity by the DTO operating as a whole (i.e., working closely with another DTO), requiring widespread action by the DTO’s members (i.e., fighting against a rival DTO), or a trend (i.e., increasing production of methamphetamines). Not all members need to participate in the action to make it corporate.

Interaction Effects

We can gain further insights into the DTO rationality by looking at the interaction effect of two variables—the level of actor, and the specific DTO. This analysis drills down and can provide insights into if a specific DTO’s actions are more or less rational on the corporate, small group, or individual-levels.

This current study does not include an additional analysis with an interaction effect of geographic region with level of actor or geographic region with DTO culture. This is because many of the specific DTOs primarily operate in distinct geographic areas (such as the Gulf Cartel in northeastern Mexico and the Juarez Cartel in north central Mexico), and findings would be similar to the interaction effect of specific DTOs with level of actor.

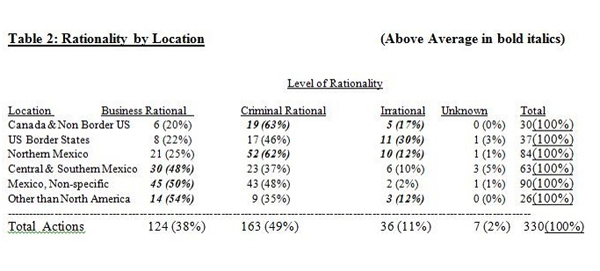

Table 2: Rationality by Location

Findings & Discussion

From the ISVG dataset, 330 separate DTO actions were identified. The analysis found that overall DTOs were more prone to business and criminal rational behavior (see table two). Out of the 330 DTO actions identified in the ISVG dataset, eleven percent (36 out of 330) of actions were irrational. This indicates that DTOs only acted irrational in one ninth of their observed actions. Thirty-eight percent (124) of the actions were business rational and 49 percent (163) were criminal rational. In the strictly business rational model, DTOs’ action adhered to business practices similar to money making practices within legitimate business over one-third of the time. Considering the broader criminal business model of rationality, that combines legitimate business and typical DTO business practices, we see that DTOs behaved rationally 77 percent of the time. Thus, these initial findings provide support to (Dell’s 2011, Widner et al. 2011’s) perspective that DTOs are rational actors.

However, the analysis found spatial variation in DTO rationality across regions (table two). The results indicate a higher propensity for irrational behavior along the US/Mexico border and a higher propensity toward business rational actions farther away from the US/Mexico border and drug distribution areas in North America. The highest propensity of DTO irrational action was in the US Border States (California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas) with 30 percent. In central and southern Mexico, 48 percent (30 of 68) of the DTOs’ actions were categorized as business rational while in additional areas other than North America (Australia, Europe, Guatemala, Ecuador, etc.), 54 percent (14 of 26) were categorized as business rational. In northern Mexico, 62 percent of all identified DTO actions were criminal rational. Overall this indicates that categorization of DTOs rationally has some variation depending on the geographic context in which they are operating. In areas where law enforcement threats were highest, there was a highest propensity for irrational action. In disputed territories, such as northern Mexico, DTOs were more likely to adhere to criminal rational actions. DTOs were most likely act business rational in areas where DTOs were most secure, such as central and southern Mexico or where they were weak and drawing attention to themselves would be dangerous such as in areas outside hemisphere where they sought to expand.

Thus, scholars when formulating DTO behavioral models should consider geographic variation in the DTOs operations. The implications for policymakers and counter-drug practioneers is that DTOs operate less rationally in certain areas (such as in high risk transit zones in the U.S. Border States) than in others (such as in reasonably safe areas of Mexico), and could require different policy, strategies and practices than those designed to increase deterrence and cost of DTO’s doing business.

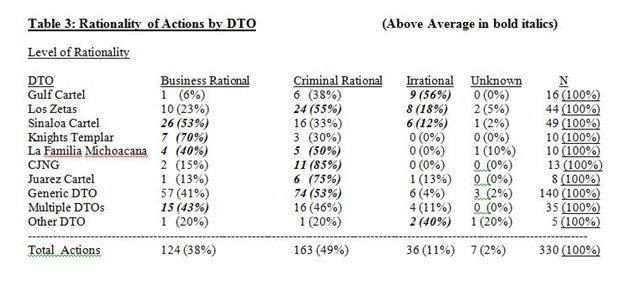

Table 3: Rationality of Actions by DTO

Looking at specific DTOs and their culture, not all data fit easily into a specific DTO. In 140 of the cases there was not enough data to classify the DTO any more specific than as a DTO, so these were labeled as “Generic DTO.” Additionally, 35 cases involved more than one DTO and were placed in the category that is labeled “Multiple DTOs.” Lastly, five DTOs we mentioned only once in the data, and were placed into the “Other DTO” label.

However the analysis did find support for variation in rationality across specific DTOs (see table three). In the Generic DTO category, most (53 percent, 74 out of 140) of the actions were criminal rational and 41 percent (57 out of 140) were business rational. Looking at specific named DTOs, the Gulf Cartel was the most prone to irrational action with 56 percent (9 of 16) of the identified action as irrational. Meanwhile, the Sinaloa Cartel and the Knights Templar actions were prone the majority of the time to be business rational. The Sinaloa Cartel’s action was business rational 53 percent of the time (26 out of 49 identified actions). The Knights Templar was business rational 70 percent of the time (7 out of 10). Additionally, LFM was overall a rational actor with 40 percent of actions (4 of 10 actions) as business rational, 50 percent as criminal rational (5 of 10 actions). Meanwhile, Los Zetas, the Juarez Cartel, and the Jalisco New Cartel Cartel (CJNG) acted criminal rationally in the majority of its identified actions (5, 75, and 85 percent respectively). These findings undermine scholars’ and practioneers’ assumption that the DTOs behave similarly, whether they are perceived as rational or irrational. This also indicates that policymakers and counter-drug practioneers should consider differing methods for combatting these different cartels. For example, deterrence would have a greater effect on more rational DTOs such as LFM and CJNG, while the deterrent model is likely less effective against more irrational DTOs such as the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas.

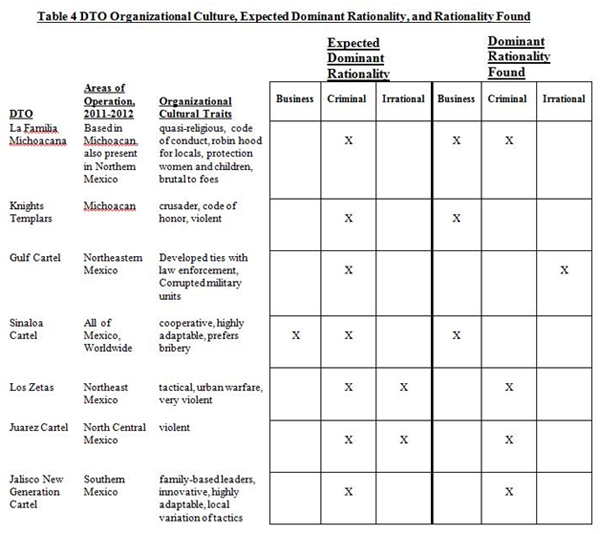

Table 4: DTO Organizational Culture, Expected and Rationality Found

In regards to our predictions of rationality based on specific DTO culture in table one, there are mixed results between what was predicted and what the data showed (see table four). The CJNG and LFM acted as predicted by being criminal rational in at least fifty percent of the cases (50 and 85 percent) while the Gulf Cartel was more irrational than predicted (56%). Likewise, the Sinaloa Cartel and the Knights Templar are more business rational (53 and 70 percent) than predicted. This demonstrates that popular understanding of these DTOs only at times stand up to empirical scrutiny, and require practioneers and policy makers to actively study their behavior prior to setting any specific policy for a specific cartel based on assumptions or popular belief.

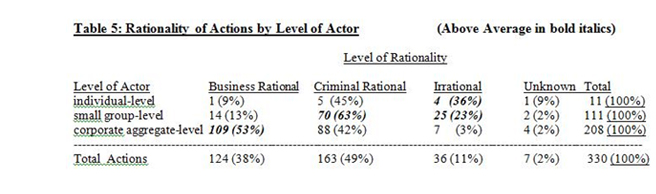

Table 5: Rationality of Actions by Level of Actor

The analysis of rationality by level of actors (e.g., individual, small group, and corporate aggregate) (see table four) reveals a pattern where DTO actions were rarely irrational for corporate aggregate-level actors as only three percent of actions were irrational (7 out of 208), and 53 percent of corporate aggregate actions (109 of 208) were business rational. Thus, DTO corporate actions were more likely rational. Meanwhile, small-group level actions were more likely (63 percent, 70 of 111 actions) to be criminal rational and 23 percent (25 of 111) were irrational. Finally, individual-level actions had the highest likelihood of being irrational with 36 percent (4 of 11 actions).

This indicates a pattern where irrational actions are more likely to be committed by individual members or small groups within the DTOs, while DTOs corporately act rationally (53 percent business rational and 42 percent criminal rational). This supports Widner et al.’s (2011) insight that DTOs are made up of multiple actors. This also explains why Dell (2011) could find that DTOs act rationally when choosing routes as she is looking at corporate aggregate actions while and how other observers have noted with anecdotal evidence DTOs action that is irrational. These anecdotal cases are likely conducted by individual and small groups. For policy makers and counter drug practioneers, these finding indicate that on the corporate aggregate level, DTOs can be seen as rational actors and weigh the costs and benefits, but they should expect the DTOs individual members and small groups to act irrationality at times, doing things that are not good for business, and not be affected by deterrence tactics.

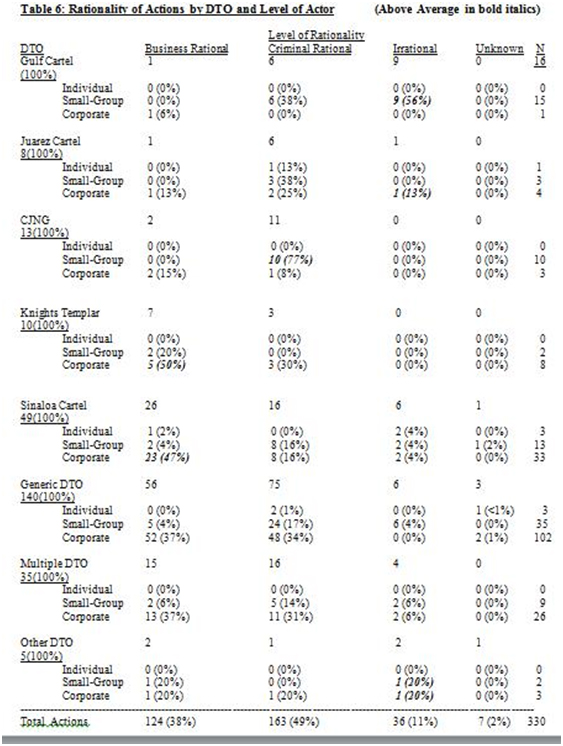

Table 6: Rationality of Actions by DTO and Level of Actor

In doing this analysis of interaction effects of specific DTOs and level of actors (see table six), the relationship between level of actor and rationality of their action is less pronounced as individual, small group, and corporate actions vary in rationality across specific DTOs. However, some patterns do exist. For the Gulf Cartel, we see small-groups’ actions account for all of their irrational action. For the CJNG, all small group actions were criminal rational. Overall this demonstrates that expectation of rationality or irrationality on corporate-aggregate, small group, and individual levels varies across DTO cultures, and varies by within a specific DTO culture by corporate-aggregate, small group, and individual levels. For policy-makers, scholars, and practioneers, this further highlights the complexity of DTO rationality, and the need to avoid blanket policies, theories, and plans based simply on deterrence.

Conclusion

Overall, this study’s findings indicate that when considering Mexican DTOs, rationality is complex and based on multiple variables such as the level of actors within the cartel, and the specific culture of each DTO, and the regional location of the DTO. First, when considering DTOs in order to predict potential future action or building theoretical models, scholars, policymakers, and counter-drug practioneers must consider the different levels of actors within the DTO. Generally, on the corporate aggregate-level, DTOs will act as legitimate businesses with cost-benefit analyses and rarely doing a purely irrational act (non-business and non-criminal rational) that would jeopardize their business interests. When considering small groups within the DTOs, these small groups are more prone to act criminal rational than business rational, and should be considered capable of acting irrational. Individual-level actors are the most prone to act irrationally, and should be considered the most unlikely to predict. Furthermore, varying levels of rationally across DTOs requires varying policy, models, and strategies tailored to the specific DTO. A policy of deterrence, increasing the costs while reducing the gains, would be most effective for specific DTOs (such as the Knights Templar, and the Sinaloa Cartel) and less effective for others (such the Gulf Cartel) but would be less effective in areas where the DTOs are most vulnerable to law enforcement (such as in the U.S. Border States) or where vulnerable to others DTOs (such as in Northern Mexico). Ironically, in areas where law enforcement capabilities are strongest, DTO are most likely to act irrationally. Ideally, future policy, models, and strategies should be devised for DTOs considering the interaction effects of level of actors, specific culture of the DTO, and regional location.

References

Becker, G. 1968. “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach.” Journal of Political Economy 76(2): 169–217.

Beittel, June S. 2013. “Mexico’s Drug Trafficking Organizations: Source and Scope of the Violence.” Congressional Research Service. April 15, 2013. Washington D.C.

Bjelopera, Jerome P. and Kristin Finklea. 2014. “Domestic Federal Law Enforcement Coordination: Through the Lens of the Southwest Border.” Congressional Research Service. June 3, 2014. Washington DC.

Coase, Ronald H. 1937. “The Nature of the Firm.” Economica, 386-405. Reprinted in Kronman, Anthony T. and Richard A Posner (eds) 1979. The Economics of Contract Law, Boston, Little Brown: 31-32.

Cornish, Derek B. and Ronald V. Clarke. 2002. “Analyzing Organized Crimes.” Piquero, A.R. (editor). Rational Choice and Criminal Behavior: Recent Research and Future Challenges. Routledge. New York, NY.

De Amicis, Albert. 2010. “Los Zetas and La Familia Michoacana Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs).” University of Pittsburgh: Graduate School for Public and International Affairs.

Dell, Melissa. 2011. “Trafficking Networks and the Mexican Drug War.” Working Paper, Harvard University.

Diaz de Mera. 2012. “Drug Cartels and their Links with European Organised Crime.” Thematic paper on organised crime. Special Committee on Organised Crime, Corruption and Money Laundering (CRIM) 2012-2013. September 2012. Accessed 15 July 2015. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/crim/dv/diazdemera_/diazdemera_en.pdf

Felbab-Brown, Vanda. 2014. “Changing the Game or Dropping the Ball? Mexico’s Security and Anti-crime Strategy under President Enrique Peña Nieto.” Latin America Initiative

Foreign Policy. November 2014. Brookings Institute. Washington DC.

Flener, Frances. 2011. “Counternarcotics Enforcement: Coordination at the Federal, State and Local Level.” Testimony before the Ad Hoc Subcommittee on State, Local and Private Preparedness and Integration. April 21, 2009. United States Senate: Washington DC.

Grayson. George W. 2013. “The Evolution of Los Zetas in Mexico and Central America: Sadism as an Instrument of Cartel Warfare.” Strategic Studies Institute. U.S. Army War College: Carlisle Barracks, PA.

Guerrero-Gutierrez, Eduardo. 2011. “Security, Drugs, and Violence in Mexico: A survey.” 7th North American Forum, Washington DC.

Hart, Oliver. 1989. “An Economist’s Perspective on the Theory of the Firm.” Columbia Law Review. 89 (7): 1757-1774.

Housworth, Gordon. 2011. “Mexico Criminal Gangs are Rational Actors.” Borderland Beat. September 2011. http://www.borderlandbeat.com/2011/09/mexico-criminal-gangs-are-rational.html

Immigration Policy Center. 2014. “The Growth of the U.S. Deportation Machine. American Immigration Council. Accessed July 11, 2015. http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/just-facts/growth-us-deportation-machine

Insight Crime. 2015. Sinaloa Cartel. Accessed July 20, 2015. http://www.insightcrime.org/mexico-organized-crime-news/sinaloa-cartel-profile

Lee, Brianna. 2014. Mexico Drug War. Council on Foreign Relations. March 15, 2014. Accessed 15 July 2015. http://www.cfr.org/mexico/mexicos-drug-war/p13689

Manwaring, M.G. 2007. A Contemporary Challenge to State Sovereignty: Gangs and other Illicit Transnational Criminal Organizations in Central America, El Salvador, Mexico, Jamaica and Brazil. Security Studies Institute of the US Army War College. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Marongiu, P., & Clarke, R. 1993. “Ransom Kidnapping in Sardinia: Subcultural Theory and Rational Choice.” Clark, R., & Felson, M. (Eds.). Advances in Criminological Theory Volume 5. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Press.

Linnenluecke, Martina K., Sally V. Russell and Andrew Griffiths. 2009. “Subcultures and Sustainability Practices: The Impact on Understanding Corporate Sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment. 18:432–452.

Masucci, David J. 2013. “Mexican Drug Activity, Economic Development, and Unemployment in a Rational Choice Framework.” Student Pulse: An International Student Journal. 5(9):1-5. http://www.studentpulse.com/authors/1461/david-j-masucci

Perez Caballero, Jesus. 2014. “How the Jalisco Cartel Evolved with Mexico's Drug War.” Insight Crime. October 15, 2014. Accessed 15 July 2015.

Ramsey, Geoffrey. 2011. “Mexican Drug trafficking organizations and the Limits of Rational Choice.” Insight Crime. December 2, 2011.

http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/mexican-drug-cartels-and-the-limits-of-rational-choice

Sackmann S.A. 1992. “Culture and Subcultures: An Analysis of Organizational Knowledge.” Administrative Science Quarterly. 37(1): 140–161

Shirk, David. 2011. “Drug Violence and State Responses in Mexico.” Unpublished Manuscript: University of San Diego.

Simon, Herbert S. 1978. “Rational Decision-Making in Business Organizations.” Nobel Memorial Lecture. Carnegie-Mellon University. 8 December 1978.

Simpson, Sally S., Nicole Leeper Piquero, and Raymond Paternoster. 2002. “Rationality and Corporate Offending Decisions.” Pp. 25-40 in Piquero’s, A.R.(editor). Rational Choice and Criminal Behavior: Recent Research and Future Challenges. Routledge. New York, NY.

Smith, Michael. 2012a. “Organization Attributes Sheet: Cartel de Jalisco Nueva Generacion.” University of Pittsburgh. Matthew B. Ridgeway Center for International Studies. Accessed 15 July 2015. http://research.ridgway.pitt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/NuevaGeneracionPROFILEFINAL.pdf

Smith, Michael. 2012b. “Organization Attributes Sheet: Juarez Cartel (Vicente Carrillo Fuentes Organization).” University of Pittsburgh. Matthew B. Ridgeway Center for International Studies. Accessed 15 July 2015. http://research.ridgway.pitt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/JuarezDTOPROFILEFINAL.pdf

The New York Times. 2012.Cocaine Incorporated. June 15, 2012.

Widner, B., Reyes-Loya, M.L. & C.E. Enomoto, C.E. 2011. “Crimes and Violence in Mexico: Evidence from Panel Data.” The Social Science Journal, 48: 604-611.

Vazquez del Mercado, Guillermo. 2012. “Organization attributes sheet: Arellano Felix Organization AFO aka Tijuana Cartel.” University of Pittsburgh. Matthew B. Ridgeway Center for International Studies. Accessed 15 July 2015. http://research.ridgway.pitt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/ArellanoFelixOrganizationPROFILEFINAL.pdf

About the Author(s)

Comments

Rationality is a weakness…

Rationality is a weakness. It's like a chocolate chip cookie that's just so darn good, you can't help but finish it. My point is, logic and reasoning are important, however when done at the expense of emotion or action they do more harm than good. So you can get the best realtors sacramento ca tips for their construction work. You see, when using logic and reasoning to defend a position or justify an action it allows the rational part of our brain to take over and make us feel great in the process.